Big Serge Thoughts

26 Apr 2024 | 4:55 pm

1. Maneuver, Position, Attrition

It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

~ Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

It is undeniably true that war is among man's oldest preoccupations. The evidence is abundant that war is essentially as old as mankind's political life, predating cities and sedentary society. It seems that man took recourse to organized violence almost as soon as he grew to a socio-political pattern of life, and from that early period much of human political and technical innovation was spurred on by the relentless drive to fight and win.

Almost as soon as war graduated past its tribal phase, it seems that man stumbled upon his next great tradition - not a tradition quite as old as war, but nearly so. The oldest battle for which we have recorded details on battlefield movements (thus the oldest battle that can be reconstructed in some level of detail) was the Battle of Kadesh, fought between the Egyptian Pharoah Ramesses the Great and the neighboring Hittite kingdom. The climax of this battle was a heroic and audacious maneuver by Ramesses, who led a battlegroup of charioteers on a ride around the battlefield to attack the Hittites on the flank.

It thus seems that for nearly the entire history of warfare (which is to say the history of man), armies have been attempting to get a powerful grouping of combat power mobile, move it to the enemy flank, and attack it immediately. Such maneuver sits at the nexus of those two powerful coefficients of battle - rational calculation and emotive aggression. Warfare constantly mediates between these two, balancing the strategic benefits of planning with the initiative and vigor of instinctive aggression. Maneuver sits at the crossroads and harnesses their powers synergistically, promising victory through initiative, decisiveness, and aggression.

Yes, armies have been lusting for the enemy flank for millenia, but technical factors often frustrate their efforts to get there. Maneuver waxes and wanes as a battlefield expedient, at times kneecapped by various technical or material constraints, be it shortcomings in logistics, command and control, or the protection of assets on the move. Operational maneuver in particular has frequently gone through long periods of technical sterility. Today in Ukraine, the ability of both combatant armies to strike staging areas and troop concentrations has forced a re-emphasis on dispersion and concealment. With maneuver once again at a crossroads in Eastern Europe, we can conclude this series by considering maneuver in its eternal relation to the military arts writ large.

Trapped in TheoryHaving made a long an arduous walk through the timeline, we see disparate instances of the military art splattered like a temporal collage of violence. What is it that unifies the body of examples? Is there a conceptual connection between the oblique order of the Thebans at Leuctra, the Mongol flying columns in Persia, Napoleon's corps movements, and the Wehrmacht's panzer package? Is there a unifying theory of maneuver at all?

Maneuver, in the simplest terms, is the use in warfare of movement relative to the enemy to gain some advantage. However, as in all areas of human endeavor, definitions themselves can become battlegrounds. Maneuver has meant different things in different ages, and in the modern age has become the subject of self-conscious debate - as, for example, in the case of the US Marine Corps' internal wrangling over the "Maneuverist" school of warfare. It is easy to get bogged down in these arguments, or to come away thinking that "Maneuver", like obscenity, is something that we cannot define, but we know it when we see it.

Modern sensibilities of maneuver - particularly those of the American military - are in fact almost unrecognizable from earlier concepts. In particular, modern theories are intensely battle-centric and focused heavily on the use of tempo and initiative to disrupt the enemy's ability to process and fight. Furthermore, in the modern parlance, maneuver is held to be essentially the opposite of positional fighting; the former is mobile and decisive, the latter is static and incremental. Such a schema would have been alien to the great generals of the early modern era. In the era of early modern warfare "maneuver" meant something very different, being both distinct from recognizably active battle and intrinsically tied to position, rather than being opposed to it.

An example would likely help, and the best comes from the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). A little studied and little appreciated war today, this was nonetheless a war of colossal import and great military interest - fought (at the risk of fantastical reductionism) to determine the balance of power in Europe between the Hapsburgs and the French, with the British backing the Hapsburgs to contain an increasingly powerful France from establishing continental hegemony.

In any case, the military aspects of the war are fascinating, because cosmetically it would appear to be a static and attritional conflict. Battles were linear, head on affairs (as was typical in the era of early musketry), and the front lines (which largely ran through modern Belgium) were dominated by complex networks of fortresses and earthworks. When viewed at satellite scale, this looked like a more primitive variation of World War One, with small territorial changes, powerful fortifications, and an apparently positional-attritional character.

In fact, the War of the Spanish Succession featured three of history's most gifted generals, including one from each of the primary combatants: Prince Eugene of Savoy for the Hapsburgs, John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough for the British, and Marshal Claude Louis de Villars for the French (shorthanded simply to Prince Eugene, Marlborough, and Marshal Villars). All three are recognized by historians as supremely talented commanders, with sensibilities that they would have clearly defined as "maneuverist."

The essence of campaigning in the WoSS was a complex series of marches and countermarches designed to lever the enemy out of position or create otherwise favorable circumstances for positional improvements. In such an operating, environment, however, the lines between maneuver and positional fighting were easily blurred. Let us take two notable examples from the career of the Duke of Marlborough, which usefully illustrate the issue.

By 1711, after a decade of war, the anti-French alliance had slowly but surely squeezed the French out of their positions in the Spanish Netherlands (as Belgium was rather confusingly called at the time), pushing the lines of contact into Northeastern France. Despite several years of setbacks, the French could feel confident in their position - the frontier was guarded by a well prepared defensive line, immodestly called the "Ne Plus Ultra Line". The line was essentially a defensive belt of rivers (many of which had been strategically dammed to raise water levels), earthworks, fences, and fortresses, with Marshal Villars prowling behind with the French Field Army. Villars felt, and not without reason, that the line was essentially impenetrable. His confidence was boosted by the unstable political position of Marlborough, who faced growing opposition back home in Britain. Villars felt that he was fighting from a position of great strength against an adversary who was under political pressure to take risks.

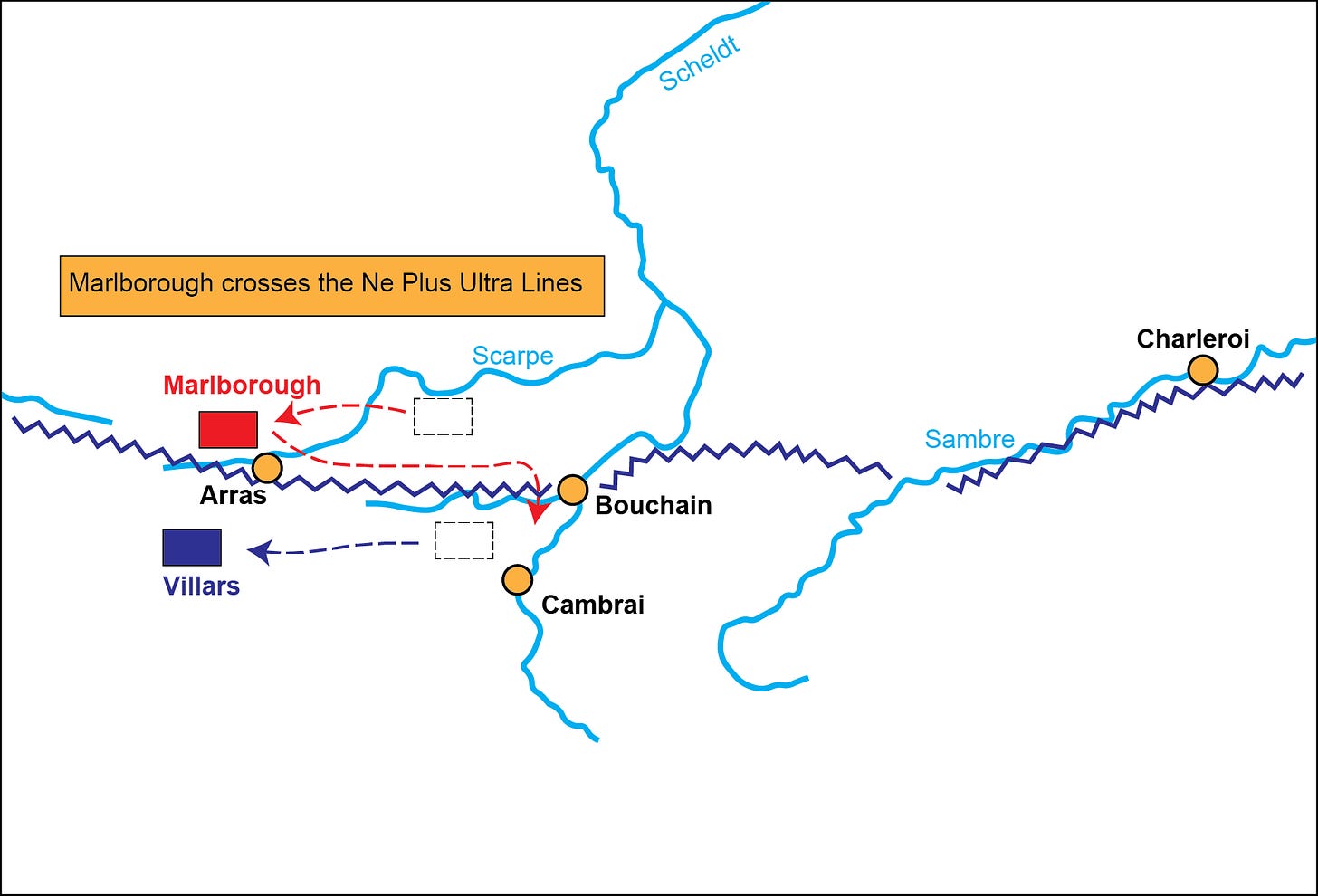

Marlborough, however, contrived a brilliant scheme to pierce the Ne Plus Ultra Line without firing a shot. Knowing that Villars' intention was to follow him laterally across the line to contest any attempt to cross, Marlborough moved west towards the fortress at Arras. Villars dutifully followed him. Marlborough then made a great show of preparing to offer battle - sending out screening cavalry detachments in full view of the enemy, and riding out with his staff to survey the terrain. French sentries observed the Duke gesturing with his cane, pointing out various terrain features and objectives to his officers. Villars implicitly believed that Marlborough would offer battle in the coming days, and sent a letter to King Louis XIV informing him that he had "brought Marlborough to his Ne Plus Ultra".

The order came down: "My Lord Duke wishes the infantry to step out." Marlborough would not offer battle - instead, he clandestinely struck camp as night fell, and began a forced march back towards the east at top speed, reaching a pre-designated crossing point over the Scheldt near the fortress at Bouchain, linking up with engineers and artillery that had been secretly positioned in wait. It was about 9:00 in the evening when Marlborough began his rapid shuttle to the east; Villars got wind that the British had gone at 2:00 AM, and though he immediately decamped in pursuit, that five hour head start was more than enough. Marlborough's forces covered over 30 miles in about 19 hours, and managed to move the entire body over the Ne Plus Ultra Line without a fight.

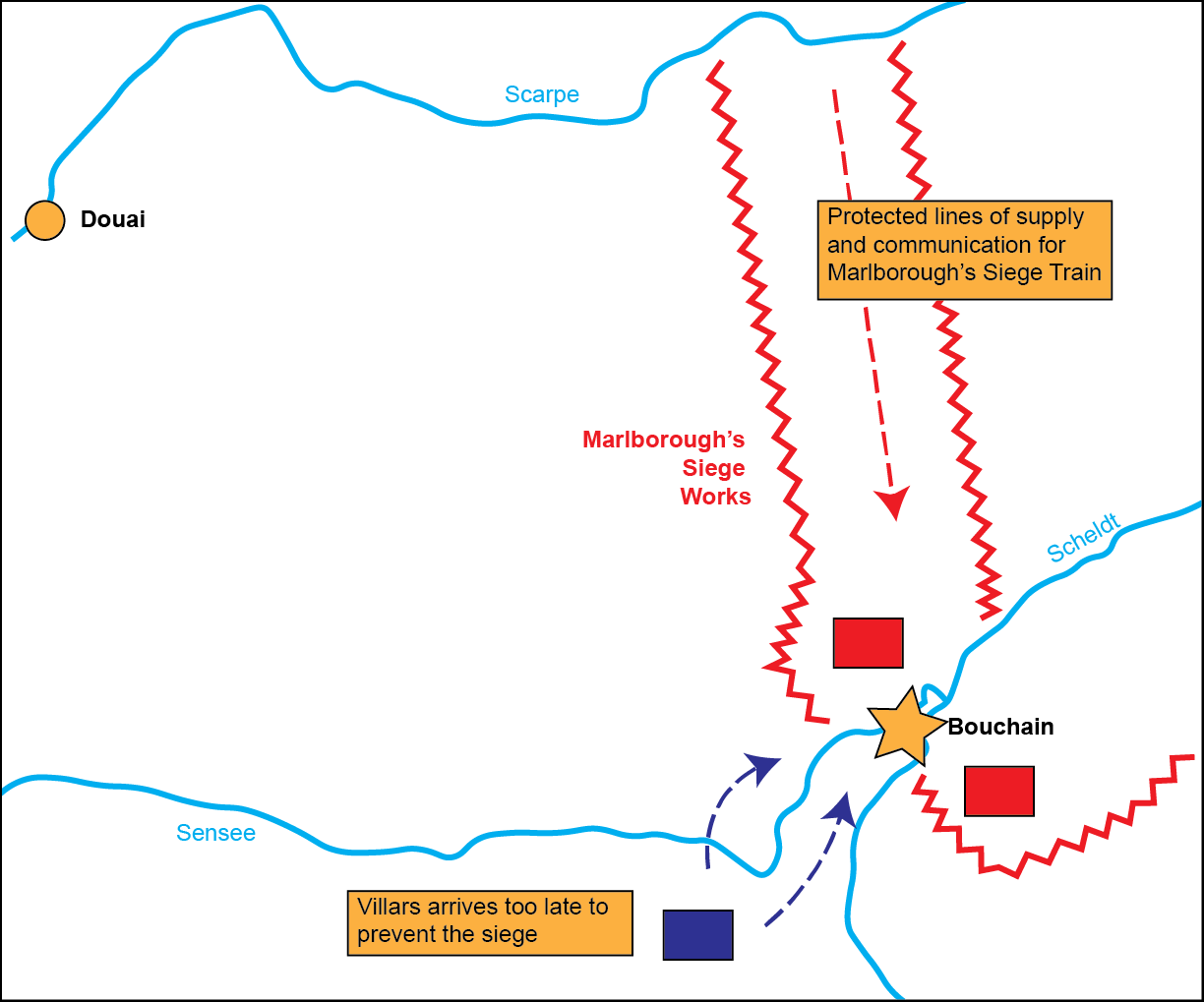

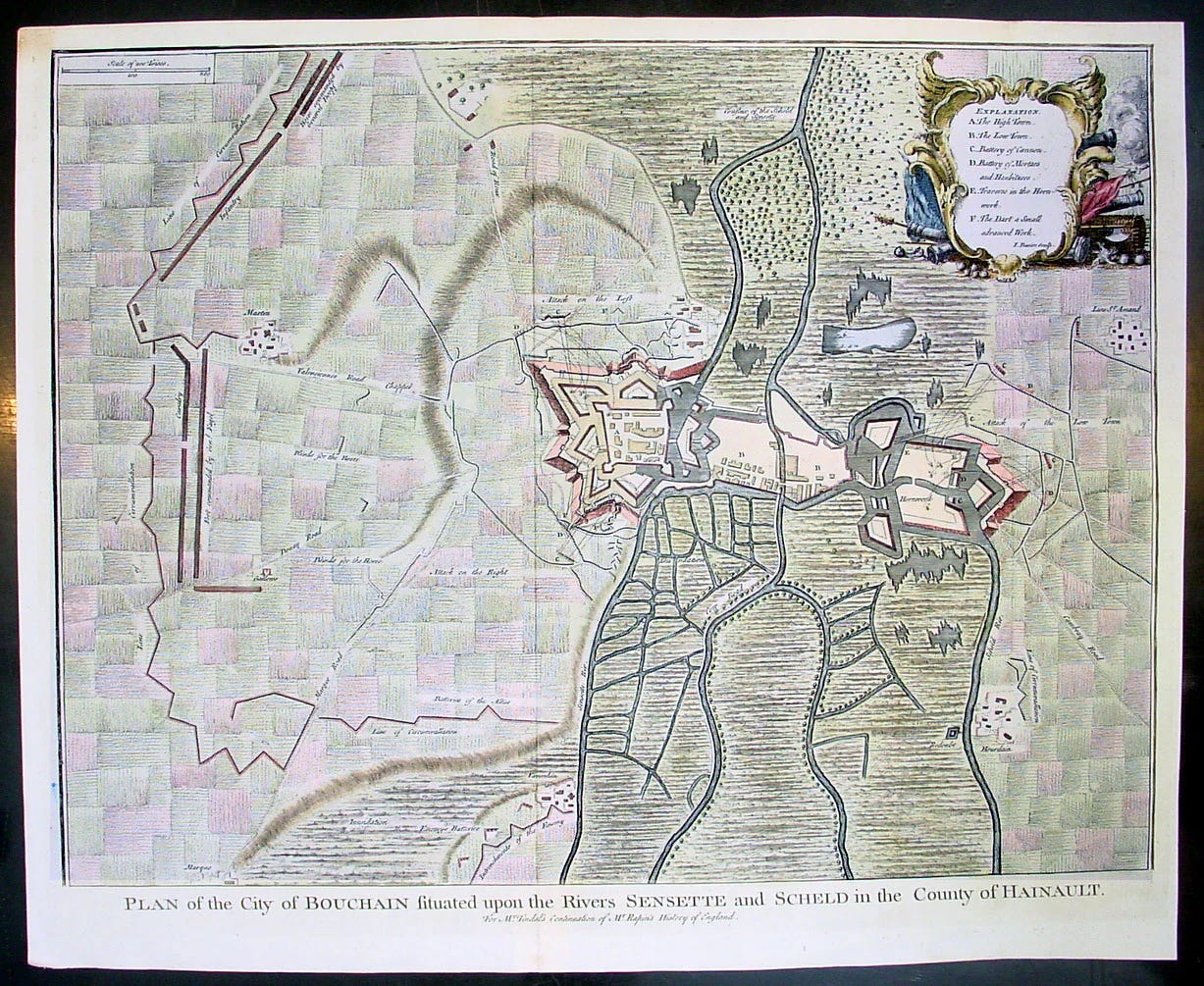

This was certainly an impressive and effective operational contrivance by Marlborough - drawing the main body of the French field army out of position with a feint towards Arras, then flying back up the road under the cover of darkness to cross the river lines near Bouchain. What seems incongruous, however, is that Marlborough used this maneuver to position himself for a siege of the Bouchain fortress. Having crossed the river lines and penetrated the French position, he set his men to work building fortifications of his own. Most importantly, Marlborough's men built a pair of long entrenchments and earthworks running back to the rear, creating in effect a protected lane of supply and communications which allowed them to haul up the ponderous and vulnerable siege train, with the enormous cannon required to reduce the Bouchain fortress.

What relation did Marlborough's Bouchain operation have to "Maneuver", as such? In the modern scheme, the fit is not immediately obvious. None of the favored motifs about tempo or aggression particularly apply. Marlborough did not "open up" the front or create a state of mobile operations. Rather, he created a window of opportunity for himself to seize an important position. The usual dichotomy of war being either mobile or positional breaks down here; maneuver for Marlborough is not an alternative to positional combat, but an enhancement to it which allows him to seize an advantageous position.

Another campaign of the Duke's, however, offers an interesting counter-example, that being the famous 1704 march to the Danube and the subsequent Battle of Blenheim. The strategic conception was fairly straightforward: the French began the 1704 campaigning season by linking up with their Bavarian allies for an offensive into the Hapsburg heartland with the intention of threatening Vienna and forcing the Hapsburgs to negotiate, thus splintering the anti-French alliance. Marlborough, who had been wintering in the Netherlands, made the risky decision to march a portion of his army all the way to southern Germany to counter the French offensive.

Marlborough's march up the Rhine has always drawn very high (and well deserved) marks from historians, for a variety of reasons.

The distance traversed was monumental for the day, with Marlborough's 20,000 strong force covering some 300 miles by foot in a month. Despite the enormous distance covered by this "scarlet caterpillar", as the long columns of redcoats were described, they arrived in the southern theater in superb fighting condition, much to the astonishment of their Hapsburg allies. This was thanks to extraordinary staff work by Marlborough and his team. The march route was carefully plotted out, and messengers were dispatched on horseback (with bags full of cash) far in advance of the main body to arrange supply depots. Consequently, the Duke's men would march into various and sundry towns on the scheduled day to find food and livestock fodder waiting for them. Marlborough thus kept his men well fed and minimized their fatigue. He even arranged to have them re-shoed, making an advance purchase to have tens of thousands of pairs of boots manufactured and delivered to Heidelberg, where the army found them waiting in enormous mounds. The precise planning of the march and the regularity of the supply were executed to near perfection.

Furthermore, the strategic redeployment entailed no small measure of risk at both the strategic and the operational level. Decamping for the Danube front left the Netherlands relatively undefended, but Marlborough accepted the hollowing out of this important front, correctly gambling that the French would not be able to exploit his absence. Furthermore, the march itself was perilous, because it necessarily involved moving laterally (that is, across the face) of the French border in marching columns. What this meant was that for an entire month, Marlborough would be presenting his flank to the enemy as he worked his way south. Again, however, the French were not positioned to capitalize.

The rapid and well-executed move to the south succeeded, without exaggeration, in saving the anti-French alliance. Linking up with Hapsburg forces under Prince Eugene, Marlborough and his allies smashed the French at the Battle of Blenheim, destroying much of a large French field army, killing its commander, and completely defeating France's southern strategy. The victory even succeeded in knocking the key French ally (Bavaria) out of the war. Blenheim is understood as a key turning point in the war which dissipated early-war French momentum.

Marlborough's 1704 campaign impresses in a variety of ways. He demonstrated a decisive instinct for command along with a bold tolerance for strategic risk, and the staff work in organizing and supplying the long march was truly exceptional. There was absolutely nothing easy or automatic about marching an early 17th century army hundreds of miles away from its supply bases, but Marlborough executed it seamlessly. Then, having successfully redeployed to the south, he fought and won a close run battle against a powerful French force. All the while, he had to manage a politically delicate coalition with the Hapsburgs. This was a classic for the ages.

But what was the relation of the Blenheim campaign to Maneuver as such? While the speed of Marlborough's movement to the south certainly evokes an impression of maneuver, in fact the campaign was simply a footrace - an attempt to reach the southern theater in a timely manner to prevent Hapsburg defeat. Marlborough did not aim to gain some advantage from movement, but only wanted to reach the decisive theater in time. The Battle of Blenheim itself was a fairly straightforward and linear field battle, with the two armies drawn up in rather classic formation. This was a display of operational mobility, to be sure, but not maneuver.

Thinking about these two operations of Marlborough - the 1704 march to the south, and the 1711 penetration of the Non Plus Ultra Line - we see that maneuver as a concept can be easily misconstrued, in particular with the modern battle-centric scheme and the aversion to positional warfare.

In 1711, Marlborough genuinely did make use of operational maneuver, using rapid lateral movement to shake off Villars and slip across the river line uncontested. In the simplest terms, he used movement to achieve meaningful advantage - however, because that advantage manifested itself in a positional siege, it would seem to be out of sync with the open and battle-centric modern schema of maneuver. In contrast, the 1704 campaign utilized rapid movement, but this was a simple matter of reaching the critical theater, rather than generating some advantage that could be levered into battlefield success.

Having suffered through this long ancillary diatribe about Marlborough, we come to the point. Maneuver and movement are not synonymous, in that some operational movements are not maneuver as such, and some maneuvers do not lead to mobility. Our general conception tends to assume that war is one or the other - position or maneuver, attrition or annihilation - but in fact these concepts can coexist quite comfortably, with maneuver empowering position and vice versa.

In the age of Marlborough, in fact, maneuver generally manifested itself as antithetical to battle, in that it could allow a force to lever the enemy out of favorable positions. For example, we may return to our old friend Marshal Villars - it is easy to feel bad for him after being juked out of position by Marlborough, but in 1712 he would have his own moment of greatness and revenge - with the anti-French coalition on the verge of victory on the northern front, Villars maneuvered his forces through a seam in the enemy positions with an audacious night march, cutting them off from their supply depots and forcing them to withdraw. With one bold maneuver, he unraveled years of coalition gains and set the stage for the compromise peace that finally ended the war.

Warfare in Marlborough's era is usually described as "limited", or "positional" in nature, often characterized by agonizingly slow and incremental gains. This was not, however, due to some doctrinal preference for position, but rather due to the logistical constraints of the era. Standing armies had become quite large, with demands for food and animal fodder that made it impossible for them to live off the land. The only way to sustain early modern armies was by assembling enormous stockpiles of food, fodder, powder, and other supplies, and running constant convoys of horse drawn wagons to haul these supplies from the depot to the field army. Given the poor state of European roads at the time, however, the range and speed of these wagon convoys was poor. Thus, the nature of the supply system kept armies tightly chained to their logistical chains and tended to keep them close to their depots, and maneuvering to threaten the links between army and depot was one of the main operational goals of all the combatants. This is why Marlborough's march to Blenheim was considered so exceptional - it remains one of the only examples of the era where an army managed to operate away from its own supply magazines.

The point here is that for generals like Marlborough or Villars, "maneuver" took on a particular meaning based on the material context of the war. The "limited" and position-oriented nature of their maneuvers was not due to some lack of vision or skill on their part, but deeply entwined with the constraints of the military system at the time.

Maneuver and position only began to separate with the later advent of the Prussian operational sensibilities and the kinetic operations of the Napoleonic era. Napoleon practiced a highly mobile and aggressive form of warfare, but it was not recognizably a form of maneuver as defined by the likes of Villars and Marlborough. To those earlier generals, maneuver was about levering the enemy by manipulating position and threatening crucial lines of supply and communications that connected enemy depots, fortresses, and field armies. Men like Napoleon and Frederick the Great, on the other hand, liked to get after the enemy at top speed and attack him immediately - on the flank, if possible, but frontally if necessary. Napoleon had little time for wriggling his way on to the enemy's supply lines - he wanted to find the main enemy field army and crush it.

Thus, the concept of maneuver expanded over time. Napoleon did not always use positional manipulation to defeat the enemy. Sometimes - as in the case of the famous Ulm Campaign - he would use a Marlboroughean (is that a word?) form of maneuver, to lever the enemy into surrender, but often he simply attacked frontally in a conventional field battle and smashed the enemy with the superior French tactical package and his own magisterial feel for command.

Modern theorists, like John Boyd, finally offered the conceptual framework to expand the definition of "maneuver" to include the generalship of men like Napoleon and Frederick. The key, according to this American school of thought, is in tempo, speed, and the disruption of the enemy's ability to process information and make decisions. Napoleon's operations were a form of maneuver because the French army used its superior speed and agility to disrupt the enemy's deployment and command.

The American theorist William Lind (a disciple of Boyd), who wrote the self-importantly titled "Maneuver Warfare Handbook" even went so far as to argue that operational maneuver was exclusively about time, speed, and cognitive processing. He noted in that 1985 book that that the Soviet doctrinal guidelines defined maneuver as "the organized movement of troops during combat operations… for the purpose of taking an advantageous position relative to the enemy." Marlborough and Villars are nodding, but Lind disagreed. Maneuver, he insisted, was not a question of spatial arrangements or position, but mental processing, and maneuver warfare was the art of acting and thinking faster than the enemy.

"But Serge, you onerously verbose rapscallion", I hear you say. "Why does any of this matter? Is theory really that important? Isn't this just an obscure debate among historians?" Well yes, I reply, but theory does matter a great deal, because it creates the cognitive architecture that militaries take to war. Armies become trapped in their theoretical animuses, which prime them to view warfare in a particular way. Misinterpreting the past to shoehorn events into a predetermined theoretical framework is often a path to battlefield difficulties or even defeat.

The German officer corps provides a poignant example of this. In the interwar period, the vestiges of the German army did an extensive amount of navel gazing, contemplating where they had gone wrong and how the first world war could have been lost. This period of soul searching reinforced the sense that war had to be fought in a mobile, attacking way - concepts from the the German operational tradition, like Schwerpunkt, Concentric Attack, and the fetishization of mobile operations became ever more deeply entrenched.

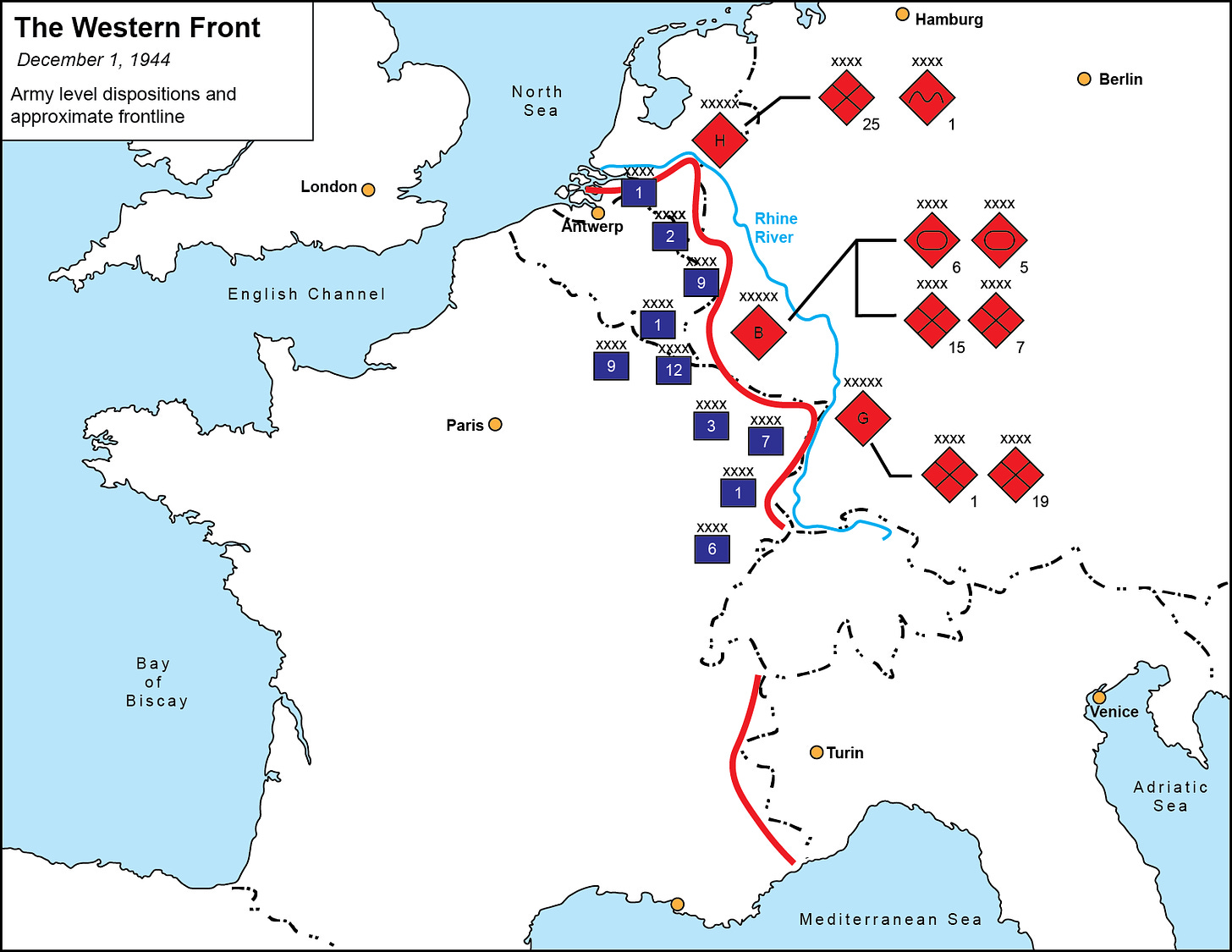

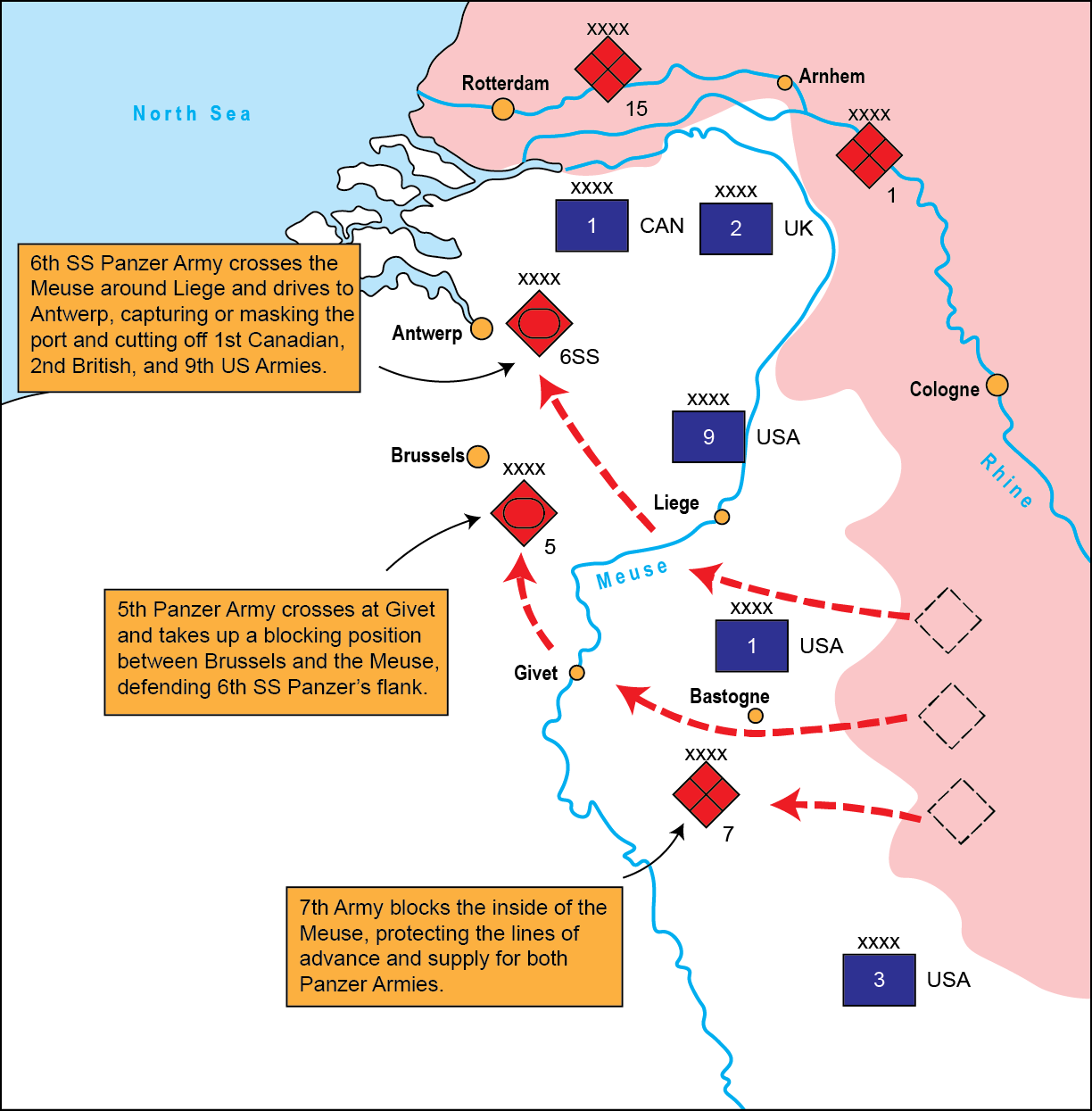

When this system worked, it worked brilliantly. German operational sensibilities and aggression carried the Wehrmacht agonizingly close to victory, churning its legs to the end at Moscow, in the Caucasus, and in North Africa. However, during the second half of the war the Wehrmacht increasingly looked like an army trapped in an alternate reality, enslaved to its own doctrine and historical self-conception. The late war history of the Wehrmacht is littered with operational schema that no longer made any sense - counterattacking the beach at Salerno, or the Mortain Gap in Normandy, or drawing up a phantasmagorical counteroffensive through the Ardennes in late 1944.

In the comfort of our hindsight, it is easy to dismiss ideas like "Schwerpunkt", or "Concentric Operations", or any of these other buzz words as simply artifacts of history - obscure lexical curiosities for military historians to throw around. They are that, but they were once more. These words and concepts were central to the way that German officers viewed and fought the war. They are splattered across the war diaries of the Wehrmacht and embedded in their orders and maneuver schemes. A unifying theory or doctrine of warfare is important for a military, because it provides a cohering intellectual framework that allows the officer corps to see and interpret events the same way, and thus act in a more unified manner. However, these theories and doctrines can easily become traps when they no longer correspond to the physical substrate of the war, and the events of recent decades have shown us just how fast that substrate can shift.

Maneuver's Eternal ReturnThe American military establishment spent the post-Vietnam decades thinking intensely about how to fight a major ground war, particularly in Europe, under peculiar cold war conditions. The fruits of this American reinvention were a reinvigorated training regimen, an array of new weapons systems and vehicles, and a totalizing commitment to agile command and control, strategic use of deep fires, and mobile operations.

Fortunately, the wargaming of the cold war remained an intellectual exercise only, and there was never occasion to test American doctrines and systems against massed Warsaw Pact tank armies. The Fulda Gap remained at peace, and Mikhail Gorbachev opted to unravel the Soviet Union with a series of self destructive political reforms. The bipolar world collapsed, as if spontaneously, into a temporary moment of unipolarity and utter American hegemony, and the American military was left holding an enormous hammer with nothing to smash.

Hence, the Gulf War - an unrivaled display of profligate military supremacy. America's Desert Storm stands at the pinnacle of the military art; a surgical, almost surreal dismantling of the adversary. America and her coalition axillaries destroyed, in the course of only a few weeks, the 4th largest army in the world, shattering a million man Iraqi army at the cost of fewer than 300 dead among the entire coalition, and a mere 148 Americans. The "kill ratios" were astonishing: something on the order of 70-1 in personnel and 80-1 in armored vehicles. In a sense, it appeared that the United States had "solved" conventional war, winning total victories at near-zero cost.

In hindsight, of course, it was easy to point out all manner of deficiencies in the Iraqi military which betrayed it to be a vast, but overmatched force. Iraqi command and control, morale, training, integration of fires, field grade command, and small unit tactics were exposed as utterly inadequate, and American forces enjoyed critical technological advantages, such as its airborne electronic warfare and ISR platforms, precision guided munitions, and the superlative fire control system on the M1 Abrams tank, which allowed American tankers to trade at exorbitant ratios when dicing it up with Iraqi armor.

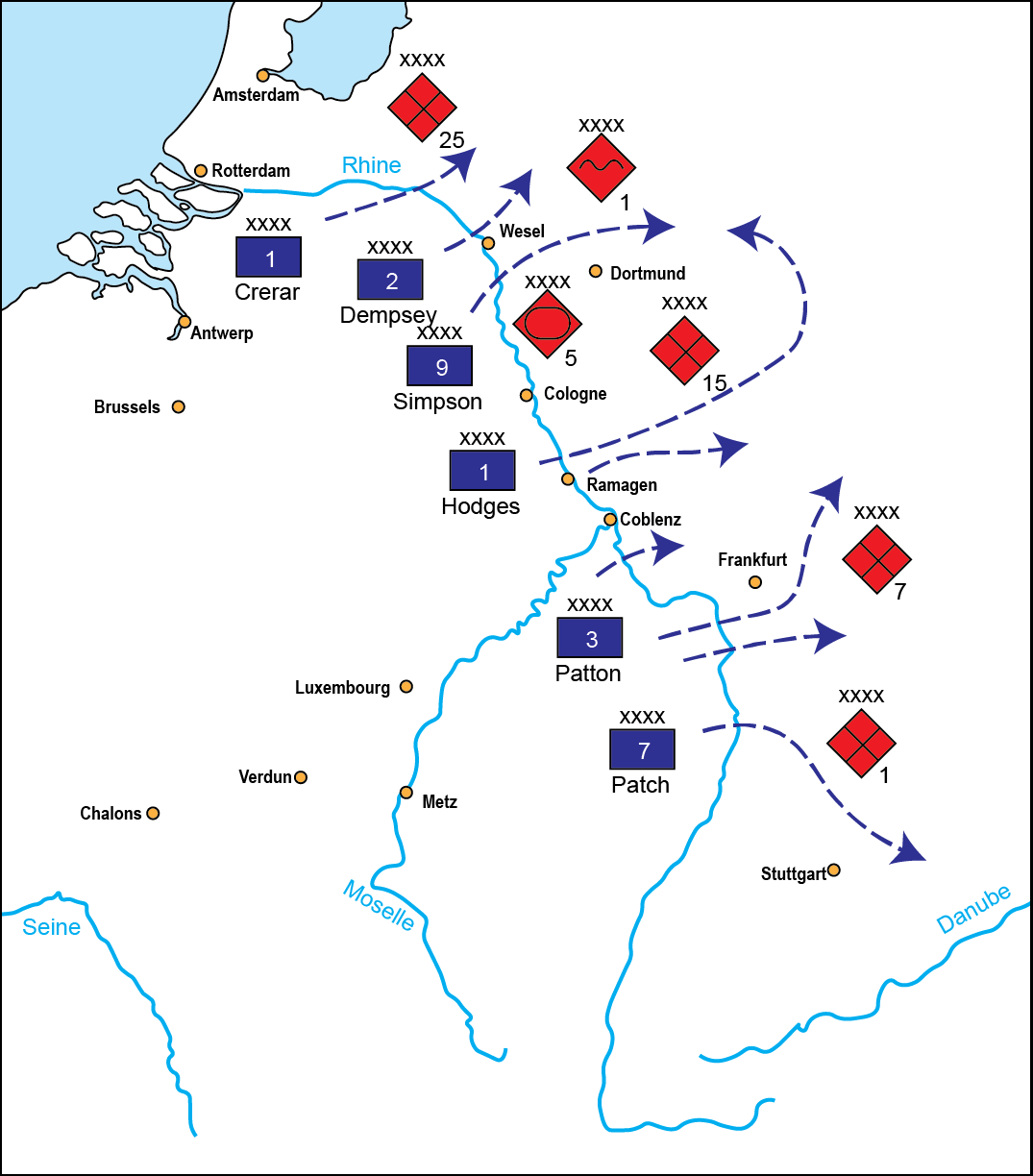

It is probably fair to say that American and coalition forces enjoyed decadent advantages in virtually every dimension of combat effectiveness, including the technological, the institutional, and the human. All that being said, however, the Coalition campaign was extremely well organized, and this fact greatly augmented the inherent advantage in combat effectiveness. The situation can be somewhat compared to the German conquest of Poland in 1939 - Germany had insuperable military advantages, but a well designed maneuver scheme allowed the Wehrmacht to leverage the biggest and most overwhelming victory possible.

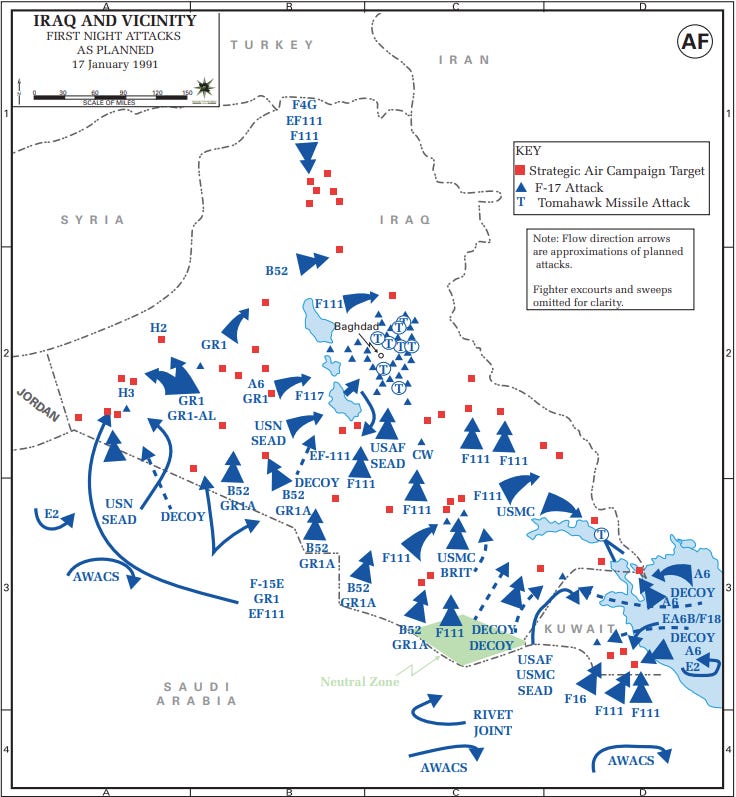

The Gulf War saw two distinct phases: a strategic air campaign (the first modern air campaign at scale against an enemy with an integrated air defense) and a maneuver campaign. We can consider the characteristics of each in turn.

The coalition Strategic Air Campaign (with over 90% of the sorties provided by American aviation) had a powerful shaping effect, in that it degraded and paralyzed Iraqi capabilities at both the strategic and operational level. Strategic targets included power generation, road and rail infrastructure, government offices in Baghdad, and industrial facilities - closer to the battlefield, critical targets like air defense, command and control posts, strike systems (particularly SCUD missile launchers), and communications were hunted.

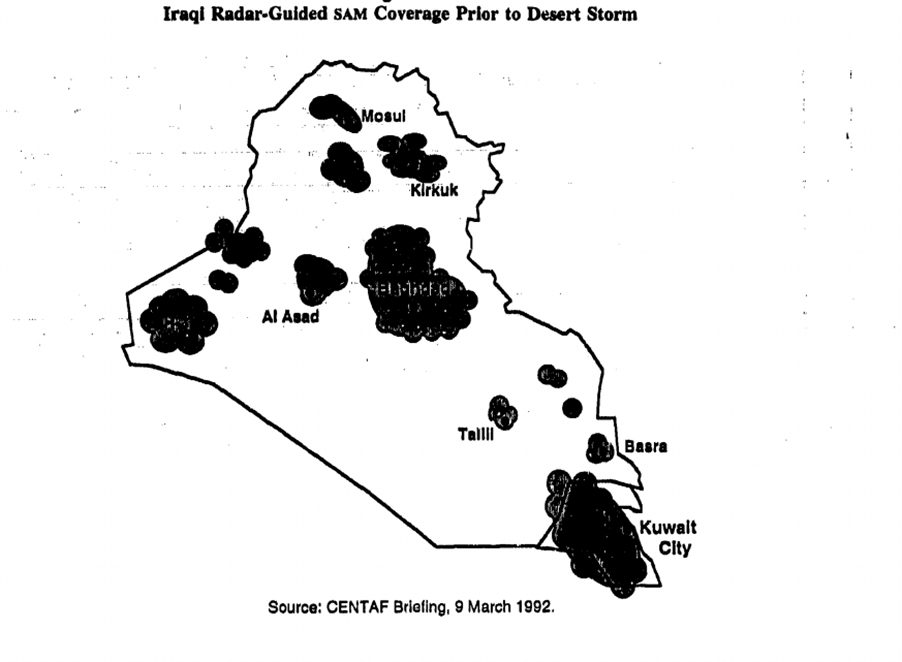

The most impressive element of the air campaign, however, was the eradication of the Iraqi air force and air defense. On paper, the Iraqis had a sizeable park of air and air defense assets, with the world's sixth largest air force (parked in specially built hardened aircraft bunkers), over 100 SAM (Surface to Air Missile) batteries, and an integrated air defense network. The Iraqi air defense net was tied to a centralized command and control bunker which ran on a French-designed computer system called Kari (the French name Irak spelled backwards). A prewar report from the Pentagon described the Iraqi air defense the following way:

The multi-layered, redundant, computer-controlled air defense network around Baghdad was denser than that surrounding most Eastern European cities during the Cold War, and several orders of magnitude greater than that which had defended Hanoi during the later stages of the Vietnam War. The multi-layered, redundant, computer-controlled air defense network around Baghdad was denser than that surrounding most Eastern European cities during the Cold War, and several orders of magnitude greater than that which had defended Hanoi during the later stages of the Vietnam War.

In fact, this was rather overly generous. The size of the Iraqi defense system belied a variety of major problems. First and foremost, Iraqi defense batteries were deployed in a point-defense role, creating clusters of air defense around strategic targets (particularly Baghdad and the invading Iraqi forces in Kuwait) with enormous gaps that allowed easy penetration of Iraqi airspace.

2 Apr 2024 | 3:19 pm

2. Index of Articles

For ease of reference, I will endeavor to keep this list updated with all the articles published here, ordered chronologically by topic or series.

Russia-Ukraine WarSound and Fury: Nukes and Force Generation Problems (Oct 28, 2022

Surovikin's Difficult Choices: Russian Kherson Withdrawal (Nov 12, 2022)

Coming Soon

Military History: ManeuverPart 2: Dispersement, Ambiguity, and Concentric Movement (Nov 10, 2022)

Part 4: Turning Movements and the Geometry of Musket Armies (Nov 28, 2022)

Part 6: The Failure of Decisive Battle in the American Civil War (Dec 16, 2022)

Part 8: The Failure of Maneuver in the First World War (Jan 17, 2023)

Part 12: The Troubled Beginnings of Soviet Operational Art (Apr 27, 2023)

Part 13: Death Trap on the Volga: The Stalingrad Campaign (May 9, 2023)

Part 14: Death Tango in the Dnieper Campaign (June 23, 2023)

Part 16: The Eagle has Landed: America Meets the Wehrmacht (Aug 2, 2023)

Part 19: One Final Effort: Germany's Last Battle (Oct 26, 2023)

Coming Soon

Miscellaneous28 Mar 2024 | 9:23 pm

3. Maneuver Theory and the Cold War

American military supremacy is an article of faith for most Americans, granting the military a strong measure of resistance to the broad decay in the trust that people have in their public institutions. Congress, the president, courts, banks, and tech companies are all lousy and crooked in the eyes of most Americans, but the military, almost uniquely, retains the trust and support of the majority. The prevailing view remains that the American military is the best trained, most technologically advanced, most competently lead, and liberally equipped force in the world. America's colossal defense budget is practically a point of pride.

America is, to be sure, one of the great martial nations of world history. It has generally won conventional conflicts, and won them big. It retains world leading capabilities in many domains, enormous power projection, and it produces exceptional fighting men. Where Americans go wrong, however, is taking this excellence to be a law of nature. An army is not a tiger, dictated by biology to be the largest, fastest, and most powerful predator in the world. It is, rather, an institution which evolves and learns over time, developing particular patterns of war-making which may or may not be well calibrated for particular operating environments.

In the latter half of the 20th Century, during that peculiar security condition that we call the Cold War, the United States Army underwent a roller coaster of institutional change - rapidly demobilizing after the defeat of Germany, coming aghast at its own unpreparedness in Korea, and cannibalizing itself in Vietnam. By 1970, the US Army was in a state of clear crisis, with its own senior leadership increasingly concerned about their ability to win a high intensity land war. From this crisis, however, the American land force began a climb back to the apex, with a radically revamped operational doctrine, new weapons programs, and an invigorated commitment to fighting an American brand of maneuver warfare.

The Menace: Stalin in ManchuriaThe Second World War had a strange sort of symmetry to it, in that it ended much the way it began: namely, with a well-drilled, technically advanced and operationally ambitious army slicing apart an overmatched foe. The beginning of the war, of course, was Germany's rapid annihilation of Poland, which rewrote the book on mechanized operations. The end of the war - or at least, the last major land campaign of the war - was the Soviet Union's equally totalizing and rapid conquest of Manchuria in August 1945.

Manchuria was one of the many forgotten fronts of the war, despite being among the oldest. The Japanese had been kicking around in Manchuria since 1931, consolidating a pseudo-colony and puppet state ostensibly called Manchukuo, which served as a launching pad for more than a decade of Japanese incursions and operations in China. For a brief period, the Asian land front had been a major pivot of world affairs, with the Japanese and the Red Army fighting a series of skirmishes along the Siberian-Manchurian border, and Japan's enormously violent 1937 invasion of China serving as the harbinger of global war. But events had pulled attention and resources in other directions, and in particular the events of 1941, with the outbreak of the cataclysmic Nazi-Soviet War and the Great Pacific War. After a few years as a major geopolitical pivot, Manchuria was relegated to the background and became a lonely, forgotten front of the Japanese Empire.

Until 1945, that is. Among the many topics discussed at the Yalta Conference in the February of that year was the Soviet Union's long-delayed entry into the war against Japan, opening an overland front against Japan's mainland colonies. Although it seems relatively obvious that Japanese defeat was inevitable, given the relentless American advance through the Pacific and the onset of regular strategic bombing of the Japanese home islands, there were concrete reasons why Soviet entry into the war was necessary to hasten Japanese surrender.

More specifically, the Japanese continued to harbor hopes late into the war that the Soviet Union would choose to act as a mediator between Japan and the United States, negotiating a conditional end to war that fell short of total Japanese surrender. Soviet entry into the war against Japan would dash these hopes, and overrunning Japanese colonies in Asia would emphasize to Tokyo that they had nothing left to fight for. Against this backdrop, the Soviet Union spent the summer of 1945 preparing for one final operation, to smash the Japanese in Manchuria.

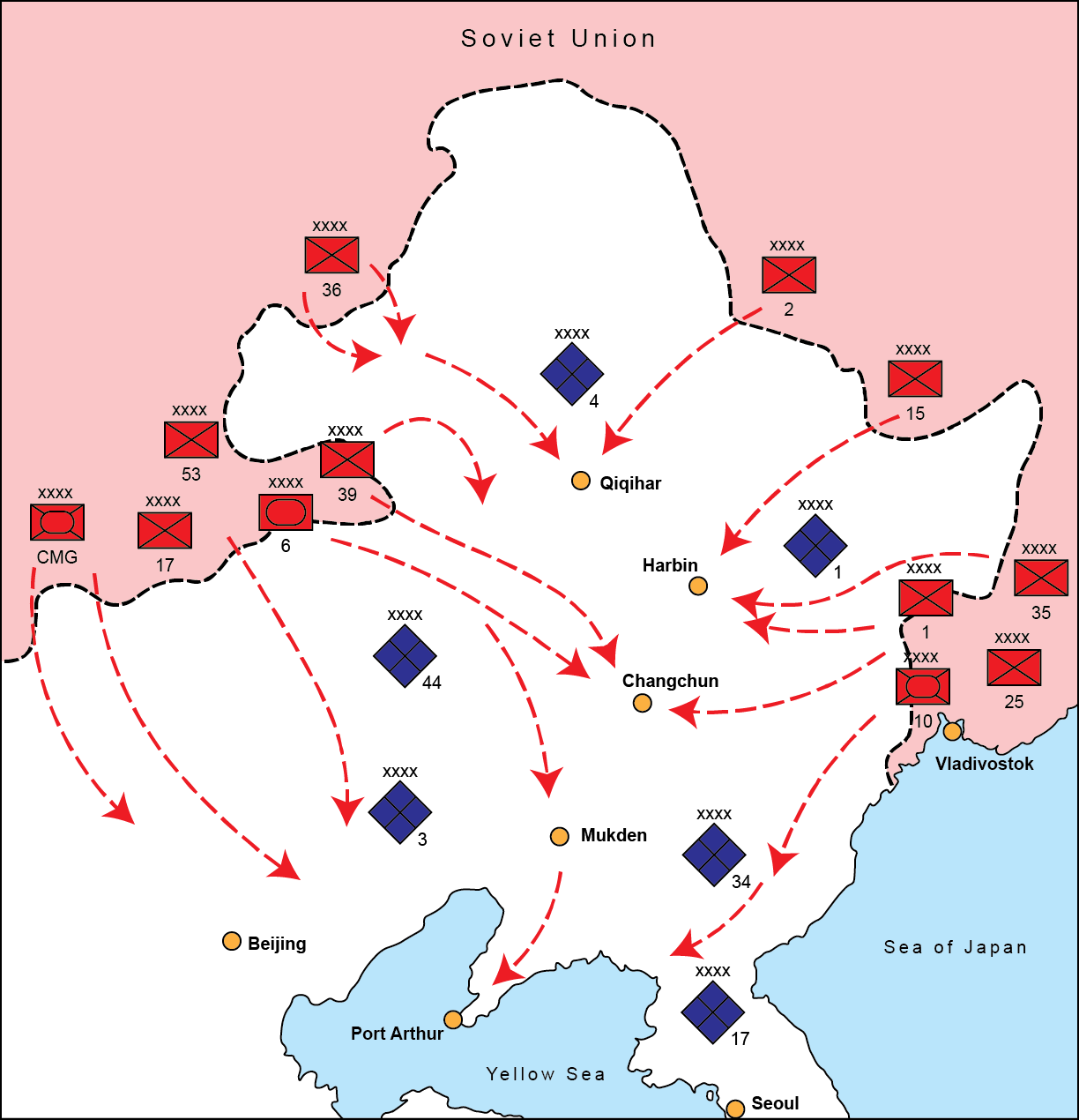

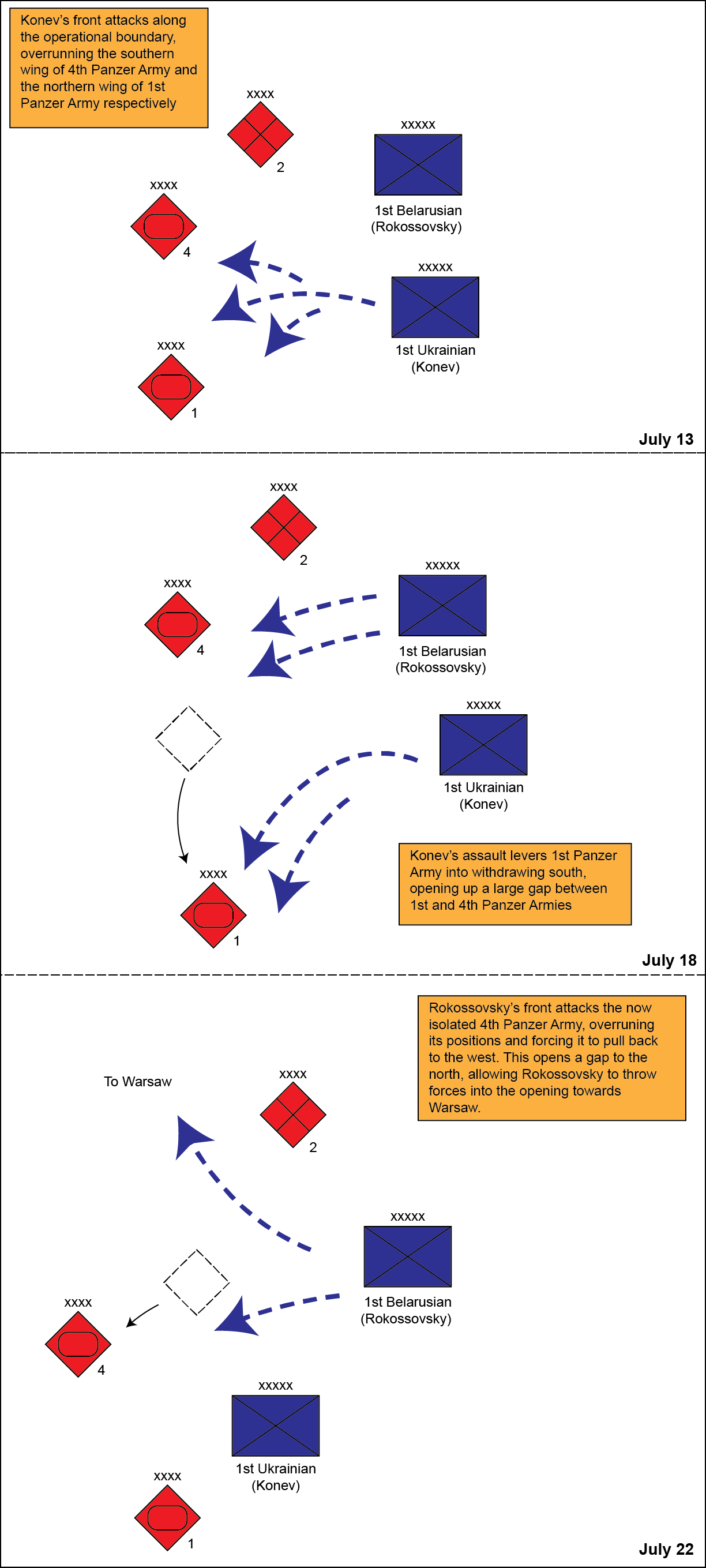

The Soviet maneuver scheme was tightly choreographed and well conceived - representing in many ways a sort of encore, perfected demonstration of the operational art that had been developed and practiced at such a high cost in Europe. Taking advantage of the fact that Manchuria already represented a sort of salient - bulging as it did into the Soviet Union's borders - the plan of attack called for a series of rapid, motorized thrusts towards a series of rail and transportation hubs in the Japanese rear (from north to south, these were Qiqihar, Harbin, Changchun, and Mukden).

By rapidly bypassing the main Japanese field armies and converging on transit hubs in the rear, the Red Army would effectively isolate all the Japanese armies both from each other and from their lines of communication to the rear, effectively slicing Manchuria into a host of separated pockets.

There were, of course, a host of reasons why the Japanese had no hope of resisting this onslaught. In material terms, the overmatch was laughable. The Soviet force was lavishly equipped and bursting with manpower and equipment - three fronts totaling more than 1.5 million men, 5,000 armored vehicles, and tens of thousands of artillery pieces and rocket launchers.

The Japanese (including Manchurian proxy forces) had a paper strength of perhaps 900,000 men, but the vast majority of this force was unfit for combat. Virtually all of the Japanese army's veteran units and equipment had been steadily transferred to the Pacific in a cannibalizing trickle - a vain attempt to slow the American onslaught. Accordingly, by 1945 the Japanese Kwantung Army had been reduced to a lightly armed and poorly trained conscript force that was suitable only for police actions and counterinsurgency against Chinese partisans.

Really, there was nothing for the Japanese to do. The Kwantung Army had far less of a fighting chance in 1945 than the Wehrmacht had in the spring of that year, and everyone knows how that turned out. Unsurprisingly, then, the Soviets broke through everywhere at will when they began the assault on August 9. Soviet armored forces found it trivially easy to overrun Japanese positions (armed primarily with archaic, low caliber antitank weaponry that could not penetrate Soviet armor even at point blank range), and by the end of the first day the Soviet pincers were driving far into the rear.

It is easy, in hindsight, to write off the Manchuria campaign as something of a farce: a highly experienced, richly equipped Red Army overrunning and abusing an overmatched and threadbare Japanese force. In many ways, this is an accurate assessment. However, what the offensive demonstrated was the Red Army's extreme proficiency at organizing enormous operations and moving at high speeds. By August 20 (after only 11 days), the Red Army had reached the Korean border and captured all their objectives in the Japanese rear, in effect completely overrunning a theater that was even larger than France. Many of the Soviet spearheads had driven more than three hundred miles in a little over a week.

To be sure, the combat aspects of the operation were farcical, given the totalizing level of Soviet overmatch. Red Army losses were something like 10,000 men - a trivial number for an operation of this scale. What was genuinely impressive - and terrifying to alert observers - was the Red Army's clear demonstration of its capacity to organize operations that were colossal in scale, both in the size of the forces and the distances covered.

More to the point, the Japanese had no prospect of stopping this colossal steel tidal wave, but who did? All the great armies of the world had been bankrupted and shattered by the great filter of the World Wars - the French, the Germans, the British, the Japanese, all gone, all dying. Only the US Army had any prospect of resisting this great red tidal wave, and that force was on the verge of a rapid demobilization following the surrender of Japan. The enormous scale and operational proclivities of the Red Army thus presented the world with an entirely new sort of geostrategic threat.

Soviet forces would begin a formal withdrawal from Manchuria and Korea in 1946, but as they receded they left in their wake consolidated and well supported communist political machines, including the Workers Party of Korea under Chairman Kim Il Sung, and the Communist Party of China under Chairman Mao Zedong. In this regard, Communism showed itself to be a much more geopolitically agile and adaptable ideology than Nazism or Japanese imperialism, as it preached a millenarian, transnational, and ostensibly scientific ideology that could motivate indigenous political parties, and the Soviet government had already developed tried and true institutional mechanisms for mobilizing resources and maintaining a political monopoly. In other words, while Nazism had always clearly been for the Germans and the Germans alone, communism could recruit and galvanize local believers around the world, and the Soviet model could give them the tools to take and hold power.

Thus, the Soviet Union presented something of a unique geopolitical triple threat. It had astonishing state capacity in its own right, in its ability to field huge armies and roll them over continent sized spaces; it had ideological penetration and appeal stemming from Communism's universalizing claims and an attractive message of social justice and scientifically ordered abundance; and it had a proven model of effective political institutions which could allow local communist parties to establish powerful political monopolies. Add it all together and you get the great menace of the Cold War: a vast and powerful Red Army that could roll over its enemies with ease, recruit enthusiastic cadres of local communists, and establish durable state structures.

All of these powers had been on full display in Asia, with the lightning advance, the rapid consolidation and funneling of resources to local communist parties, and the durable North Korean and Chinese party-states that were left behind once the Red Army withdrew. To make matters even worse, this powerful Soviet expansion apparatus was now precariously forward deployed deep in the heart of Europe, with the Soviet frontier pushing all the way into Central Germany.

The fear that the Soviet Union would replicate its Manchurian exploits in Europe became the foundational anxiety of the Cold War - predating both Soviet atomic weapons and, by extension, the fear of nuclear war. As early as 1947, France and the United Kingdom began signing joint defense pacts, which expanded to include Belgium and the Netherlands with the 1948 Treaty of Brussels, bringing about the short-lived "Western Union Defense Organization" (WUDO). It was clear, however, that such a limited alliance structure would be utterly inadequate in the event of war with the Soviet Union. France and Britain were degraded, threadbare powers in no place to fight yet another major war. One telegram sent from Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery's staff at WUDO headquarters to a liaison at the American State Department simply said:

Present instructions are to hold the line of the Rhine. Presently available forces might enable me to hold the tip of the Brittany Peninsula for three days. Please advise.

Montgomery himself, though, said it best. Asked what it would take for the Red Army to break through to the Atlantic, he simply answered:

Thinking about the UnthinkableShoes.

The transition from the end of the Second World War to the beginning of that peculiar global security dilemma which we call the Cold War is often poorly understood or even glossed over - obviously, the entire history of the late 1940's is beyond the purview of our interest in the history of maneuver doctrine and operations, but a skeletal recollection may still be useful.

The beginning of the Cold War, as such, can probably be best identified as a sequence of events in 1948 and 1949, which together represented the breakdown of the post-war Soviet-American cooperation in Europe and the consolidation of the power blocs that would characterize the Cold War. In those intervening years after the end of the Second World War, the United States and the Soviet Union undertook a series of actions designed to consolidate their positions in Europe according to the postwar settlement.

These actions took the form of both direct influence and attempts to exclude the other party from the appropriate sphere. The United States, for example, rehabilitated and integrated Western European economies under the Marshall plan while the USSR forbade eastern bloc countries from participating, fearing American economic and political penetration into its satellites. While the USSR reconstituted governments in Eastern Europe into Soviet style communist political monopolies, communists were ejected from governments in France and Italy. There was thus a certain degree of symmetry as both the USSR and the United States consolidated the two spheres of Europe, creating a sharp split down the spine of the continent.

The situation continued to spiral, with the United States intervening in Greece in 1947 to prevent a communist takeover, a 1948 Soviet-backed coup by communists in Czechoslovakia, and the subsequent Soviet abandonment of the Allied Control Council (in effect ending the primary post-war joint body for administration in occupied Germany). The culminating point of all this was an attempted communist putsch in Berlin, followed by the infamous Soviet blockade of the German capital and the Berlin airlift in the winter of 1948. It is not a coincidence that the formation of NATO on April 4 coincided with the closing weeks of the Berlin blockade and the collapse of the Allied Control Council. The formation of a formal American military bloc in Western Europe was the natural culmination of a security situation that had deteriorated with alarming speed. The Soviet Union predictably followed with the Warsaw Pact a few years later. The Cold War was on.

What matters most for our purposes, of course, is not this whirlwind sequence of events or even the breakneck bifurcation of postwar Europe into Soviet and American spheres. What is interesting to us is the fact that the onset of the Cold War presented the United States with a novel problem, namely how to plan for and think about a future war on the European Continent against the Soviet-led forces of the Warsaw Pact. This was, in fact, a very new position for the United States, which for most of its existence had maintained a relatively skeletal officer corps that did not think deeply about operations, or military doctrines at all.

The American Army had always been most unlike its European counterparts, spending most of its life as a border constabulary in the expanding American West. It was certainly nothing like, say, the Prusso-German Officer Corps, which was accustomed over the decades to theorizing, debating, planning, and simulating ad nauseum. While all the major continental armies spent the 1930's thinking deeply about armored warfare and doctrinal concepts, the US Army had no armored force at all, and the simple field regulations issued to officers had nothing to say about the matter. It was not until 1941 (after the German campaigns in Poland, France, and the invasion of the Soviet Union) that the US Army conducted its first ever operations scaled mechanized field maneuvers.

The difference between the pre and post World War Two American security dispositions could not have been more stark, therefore. While the pre-war army thought very little about continental warfare in a systemic or doctrinal way, the US Army in the Cold War was frequently preoccupied with theorizing about a future European war against the Soviet bloc. While prewar America was secure in its latent industrial power and the strategic depth provided by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, postwar America remained forward deployed in both hemispheres. Central European lands that had once been the stomping ground of Prussian and French armies now became an American security fixation.

Matters were further complicated by the entirely novel kinetic additive of atomic weapons, which gave frightening new capabilities and an uncertain use case. Throughout the cold war, both the USSR and the USA would be constantly assessing and reassessing both theirs and the other's willingness to use nuclear weaponry, and this in turn fed assumptions about how a ground war in Europe would be fought.

America's atomic monopoly did not last very long in absolute terms, but it nevertheless shaped the base of Cold War military thinking. In the years leading up to the Soviet Union's first successful atomic test in 1949, there were many assumptions made about the security that the west could derive from the American nuclear monopoly (including, most fantastically, Bertrand Russell's call for a preemptive nuclear attack on the Soviet Union). All of these assumptions were shattered by the speed at which the USSR was able to demonstrate its own atomic powers.

Paradoxically, however, the Soviet Union's 1949 atomic test did not ameliorate Soviet insecurities in the short term. This was because, although the test was an important milestone and show of force, the USSR was not able to immediately convert the test into use-ready atomic weaponry. In fact, the Soviet Air Force did not take delivery of operational atomic bombs until 1954. This meant nearly a full decade of acute atomic vulnerability which strongly shaped Soviet strategic sensibilities.

The upshot of all this was that America's atomic monopoly lasted much shorter than the United States had originally hoped and anticipated, but much too long for Moscow's comfort. The security of the early atomic monopoly allowed the United States to rapidly demobilize its armies; simultaneously, the Soviet Union hoped to lean on vastly superior conventional forces as a counterposition to the American nuclear arsenal, and those same gargantuan conventional forces deepened the sense of crippling insecurity in Western Europe.

As previously mentioned, by the late 1940's it was already clear that the limited WUDO alliance (comprised essentially of France, Britain, and the Low Countries) was simply too weak to present a credible opponent to the Soviet Union and the emerging Eastern Bloc. This sense of European insecurity only intensified between 1949 and 1951, with the successful Soviet atomic test, the victory of the communists in China, and the war in Korea. Any earnest attempt to contend with the Red Army would inevitably require the involvement of the United States.

Even with American involvement in European security via NATO (formed in 1949), there were a host of difficult and divisive issues to parse out. In contrast to the Russian perception of NATO as nothing but a tool of American foreign policy, the alliance's early history was wracked with disagreements about how to ensure European security. First and foremost was the question of Germany's role in Europe.

It was quite clear to many, particularly in America, that any credible European alliance would require the rehabilitation and integration of West Germany (formally the Federal Republic of Germany), which was formed in 1949 through the merging of the British and American occupation zones. Even after the trauma of the Second World War and the division of the country, West Germany was by far the most populous and potentially powerful country in Western Europe. It was also, rather obviously, likely to be the critical battleground in any future war with the Soviet Union. Therefore, the Anglo-Americans decided early on that the rehabilitation and rearmament of West Germany was critical for European security. This plan ran into vehement opposition from the French, who remained deeply resentful towards Germany and suspicious of any attempt to rearm them - one particularly bold French proposal even called for German infantry to be inducted into the European commands (in effect, preventing the West Germans from having any organic units higher than a battalion and subordinating them to French divisions).

In the end, it was clear that German manpower and resources would have to be fully leveraged, particularly in light of NATO's preliminary goals of fielding a 50 division army in Western Europe. Therefore, as a sop to the French, the unification and rearmament of Germany was counterweighted by additional American deployments in Europe, as a gesture of America's commitment to European defense and a guarantee that France would not soon find itself dominated once again by the Germans. The integrated NATO military command and preponderance of American influence ensured that German resources could be mobilized without granting West Germany any genuine strategic autonomy. Thus, the basic strategic arrangement of European security was established by the early 1950's, with the first General Secretary of NATO, Lord Hastings Ismay, famously observing that NATO had been structured to "keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down." Notably, however, the item about "keeping the Americans in" was viewed not as an American attempt to maintain influence in Europe, but the other way around: Europeans feared being abandoned by the Americans and wanted to ensure an American commitment to European security.

Even with all of this diplomatic and geostrategic horse trading, however, the math of force generation was simply not in NATO's favor. Even with plans to raise 12 German divisions, it was clear that NATO's 1952 decision to field a 50 division force was simply unrealistic - particularly because western leadership was loathe to risk the fragile economic recovery of Western Europe by adopting a crash rearmament program. This was plainly evident to Dwight Eisenhower, with his intimate knowledge of the European theater, and when he became president in 1953 his national security team immediately began to implement a new defense posture that aimed to use atomic weaponry as a substitute for conventional ground forces in Europe.

In the mid 1950's, therefore, NATO's war planning (really, America's) was built around a 30-division ground force which would be tasked with delaying and funneling Soviet forces into concentrated masses which would offer enticing targets for tactical (battlefield) atomic weapons, paired with a policy of so-called "massive retaliation", which promised catastrophic atomic bombing of Soviet rear areas and cities. Eisenhower's Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, said in a public 1954 speech:

We need allies and collective security. Our purpose is to make these relations more effective, less costly. This can be done by placing more reliance on deterrent power and less dependence on local defensive power... Local defense will always be important. But there is no local defense which alone will contain the mighty land power of the Communist world. Local defenses must be reinforced by the further deterrent of massive retaliatory power.

Perhaps at this point an editorial comment is warranted. Our focus in this (very long) series of articles has been the history of maneuver in warfare. It would seem warranted to ask whether we've lost the plot here, with a very long digression into the early history of NATO and America's nuclear use doctrine. This is fair enough. What we wish to establish, however, is that during the first decades of the Cold War American operational sensibilities were heavily predicated on the inevitability of atomic use, the application of atomic weaponry as a deterrent, and the battlefield uses of atomic weapons.

Almost no thought was given to winning a conventional war against the USSR. Louis A Johnson, Secretary of Defense from 1949-1950, was frank in his belief that America had practically no need for non-nuclear forces, and openly mused that the Navy and the Marine Corps out to be abolished outright. In such an environment, little thought was given to conventional operations. By the end of the 1940's, General Omar Bradley was of the opinion that the US Army "could not fight its way out of a paper bag."

This thinking was soon mirrored by the Soviets themselves, particularly with Nikita Kruschchev's 1960 address to the Supreme Soviet in which he proclaimed a new strategy of comprehensive nuclear missile warfare. Under such a framework, there was virtually no distinction between attack and defense - any conventional conflict with the west would be implicitly presumed to go nuclear, therefore the only way to fight such a war was to immediately launch an all-out ground offensive paired with nuclear annihilatory strike. As a 1960 Soviet handbook put it:

Soviet military doctrine sees concerted offensive operations as the only acceptable form of strategic actions in nuclear warfare, and stresses that strategic defense contradicts our view of the character of a future nuclear war and of the present state of the Soviet armed forces… Under modern conditions, passivity at the outset of a war is out of the question, for that would be synonymous with annihilation.

Throughout the 1960's, therefore, the Soviet Union conducted an enormous armaments program which expanded not only their own conventional and nuclear forces, but also the forces of Warsaw Pact satellites, which received over 1,200 new aircraft, 6,000 tanks, and 17,000 armored equipment in the first half of the decade. There was particular emphasis on the base of fire, with Soviet divisions expanding from 8,000 to 12,000 men to increase the size of the organic divisional artillery, and a host of new rocket brigades being provisioned for Warsaw Pact armies.

The culmination of the Soviet "60's program", if we can call it that, was the 1969 Zapad-69. The Red Army simulated a nominal "attack" by NATO, and responded with an all-out offensive by five different army groups, which went punching into West Germany, shooting over the Rhine, south towards the Swiss border, and northward into Denmark. Given the enormous preponderance of Eastern Bloc force generation, Soviet planners concluded (probably realistically) that by the fourth day of the war their spearheads would be well established on the Rhine, and NATO would resort to atomic weapons to avoid total defeat. At that point, the conventional phase of the war would be over and a full nuclear exchange would be underway.

All that is to say, that although both the USSR and the USA followed their own unique paths of strategic development, by the 1960's had come to the assumption that conventional war would lead necessarily to nuclear war. A host of different doctrinal names, like Eisenhower's "massive retaliation" and Khrushchev's "comprehensive nuclear missile warfare" all related essentially to the primacy of nuclear warfare and the growing centrality of escalation management and game theory.

In such an operating environment, there was little role for dynamic thinking about how to fight a conventional war in Europe, particularly for the US Army. Eisenhower rather explicitly viewed US ground forces as little more than a trip wire and a delaying screen that would set the stage for decisive action from the US Strategic Air demand.

Ground forces became so subordinate that the US Army Chief of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor, contrived an entirely new structure for US Army Divisions that would allow them to have organic nuclear weapons systems (an 8-inch howitzer battery equipped with atomic shells and the MGR-1 Honest John Atomic Rocket system). His rational was essentially the institutional survival of the army: nuclear war had become so fundamental to European war scenarios that Taylor believed the Army would have to carve out an atomic role for itself if it wanted to retain its budgetary and personnel access.

A conventional war of mobile operations, in the style of the Second World War, increasingly seemed like an anachronism. Mid-century American conflicts like Korea and Vietnam offered few glimpses into what a peer war in Europe would be like. Korea, after episodic periods of mobility, largely developed into a firepower intensive slugfest amid the mountainous and unfriendly terrain of the peninsula. Vietnam, of course, devolved into an infamous American military headache, but one which seemed to have few parallels to a future war in Europe. Between the focus on atomic weaponry and befuddling Asian misadventures, the world-beating US Army seemed adrift. Then the Israeli Defense Forces recieved a nasty surprise on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur.

Revival (in Theory)The Vietnam War as a major socio-political stressor for mid-century America is a well worn and well understood story. Less well known, however, was the way that the war brought the American military establishment to a state that bordered on crisis. Beginning with Lyndon Johnson's decision to fight Vietnam without mobilizing reserves or national guard (instead choosing to lean on the active force and the draft) caused the war to cannibalize and drain the active force. Meanwhile, the financial drain of the war ate away at the defense budget, to the effect that the army fielded no major new systems during the 1960's. Finally, defeat was brushed aside as a manifestation of American political failures and the peculiar nature of fighting a tropic counterinsurgency - the broad conclusion seems to have been that the military did not fail in Vietnam so much as the parameters of the war had failed to accommodate the military.

As a result, the US Army entered the 1970's with aging weapons systems, low institutional confidence, and no real lessons learned. It is not an exaggeration to say that the US Military (and the Army in particular) were at a sort of institutional nadir at this point. This happened to coincide, however, with a renewed interest in thinking about winning a conventional war in Europe, that is to say, without immediate recourse to atomic weaponry, largely due to the growth of Soviet second strike capabilities. In other words, the US Army had a sudden revival of interest in fighting a conventional ground war at exactly the time that it had the lowest capacity to due so.

1 Mar 2024 | 9:15 pm

4. Russo-Ukrainian War: The Deluge

As the calendar barrels into another year and we tick away the days of February, notable anniversaries are marked off in sequence. It is now 2/22/2022 +2: two years since Putin's address on the historic status of the Donetsk and Lugansk regions, followed on 2/24/2022 by the commencement of the Special Military Operation and the spectacular resumption of history.

The nature of the war changed dramatically after a kinetic and mobile opening phase. With the collapse of the negotiation process (whether thanks to Boris Johnson or not), it became clear that the only way out of the conflict would be through the strategic defeat of one party by the other. Thanks to a pipeline of western support (in the form of material, financial aid, and ISR and targeting assistance) which allowed Ukraine to transcend its rapidly evaporating indigenous war economy, it became clear that this would be a war of industrial attrition, rather than rapid maneuver and annihilation. Russia began to mobilize resources for this sort of attritional war in the Autumn of 2022, and since then the war has attained its present quality - that of a firepower intensive but relatively static positional struggle.

The nature of this attritional-positional war lends itself to analytic ambiguity, because it denies the most attractive and obvious signs of victory and defeat in large territorial changes. Instead, a whole host of anecdotal, small scale positional analysis, and foggy data has to suffice, and this can be easily misconstrued or misunderstood. Ukraine's supporters point to nominally small scale advances to support their notion that Russia is suffering cataclysmic casualties to capture small villages. This suggests that Russia is winning meaningless, pyrrhic victories which will lead to its exhaustion, so long as Ukraine receives everything it asks for from the west. At the same time, the Z-sphere points to these same battles as evidence that Ukraine can no longer hold even its most heavily defended fortress cities.

What I intend to argue here is that 2024 will be highly decisive for the war, as the year in which Ukrainian strategic exhaustion begins to show out at the same time that Russia's strategic investments begin to pay off on the battlefield. This is the way of such an attritional conflict, which burdens armies with cumulative and constant stressors in a test of their recuperative powers. Wear and tear and the raging of the waters will erode and burden the dike until it bursts. And then the deluge comes.

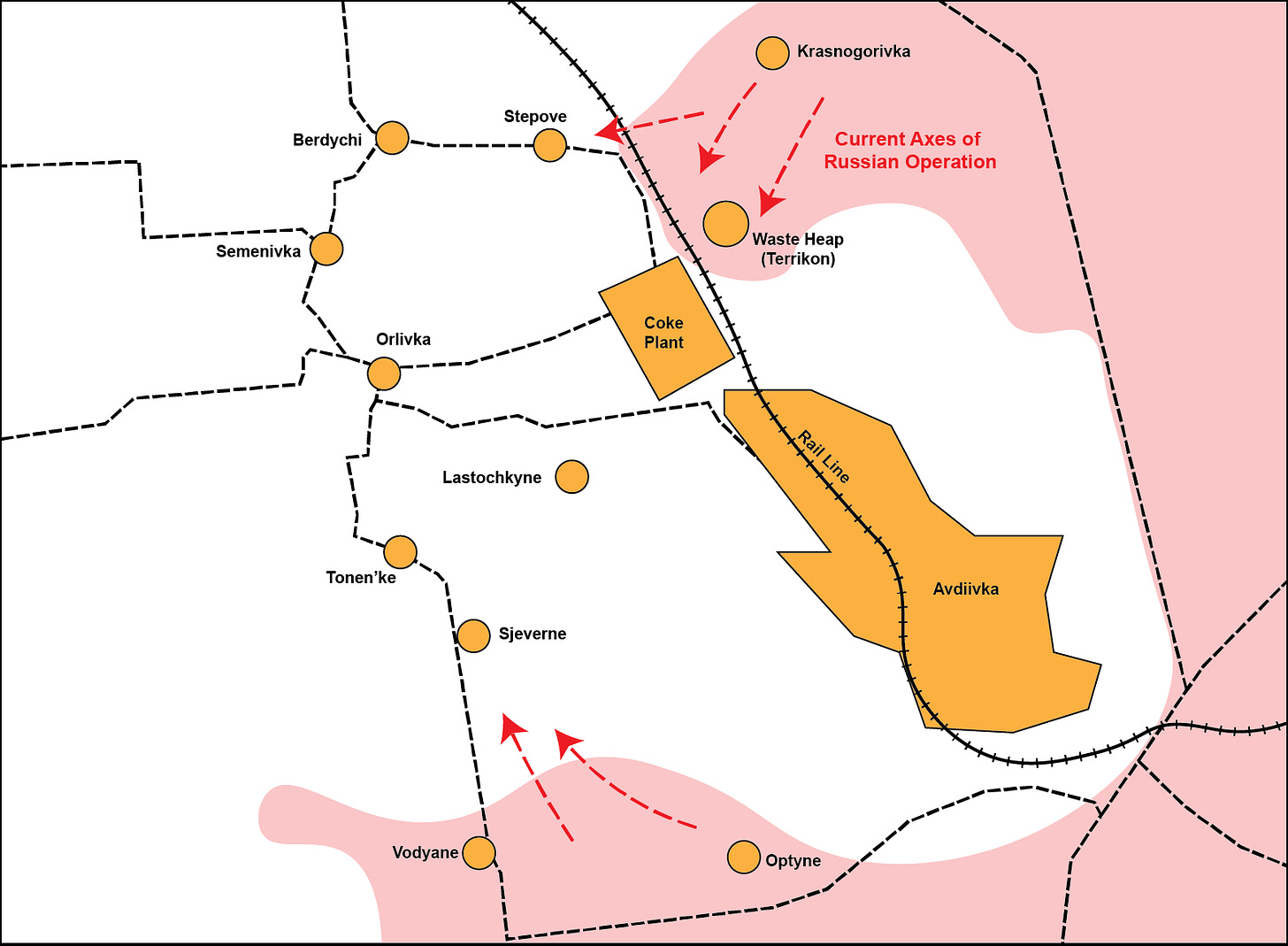

Avdiivka: Tactical OvermatchThe signature operational development of 2024 is at this point clearly the complete Russian capture of Avdiivka. The strategic significance of Avdiivka has itself been subject to debate, with some dismissing it as little more than a dingy suburb of Donetsk, targeted to give Putin a symbolic victory on the eve of Russian elections.

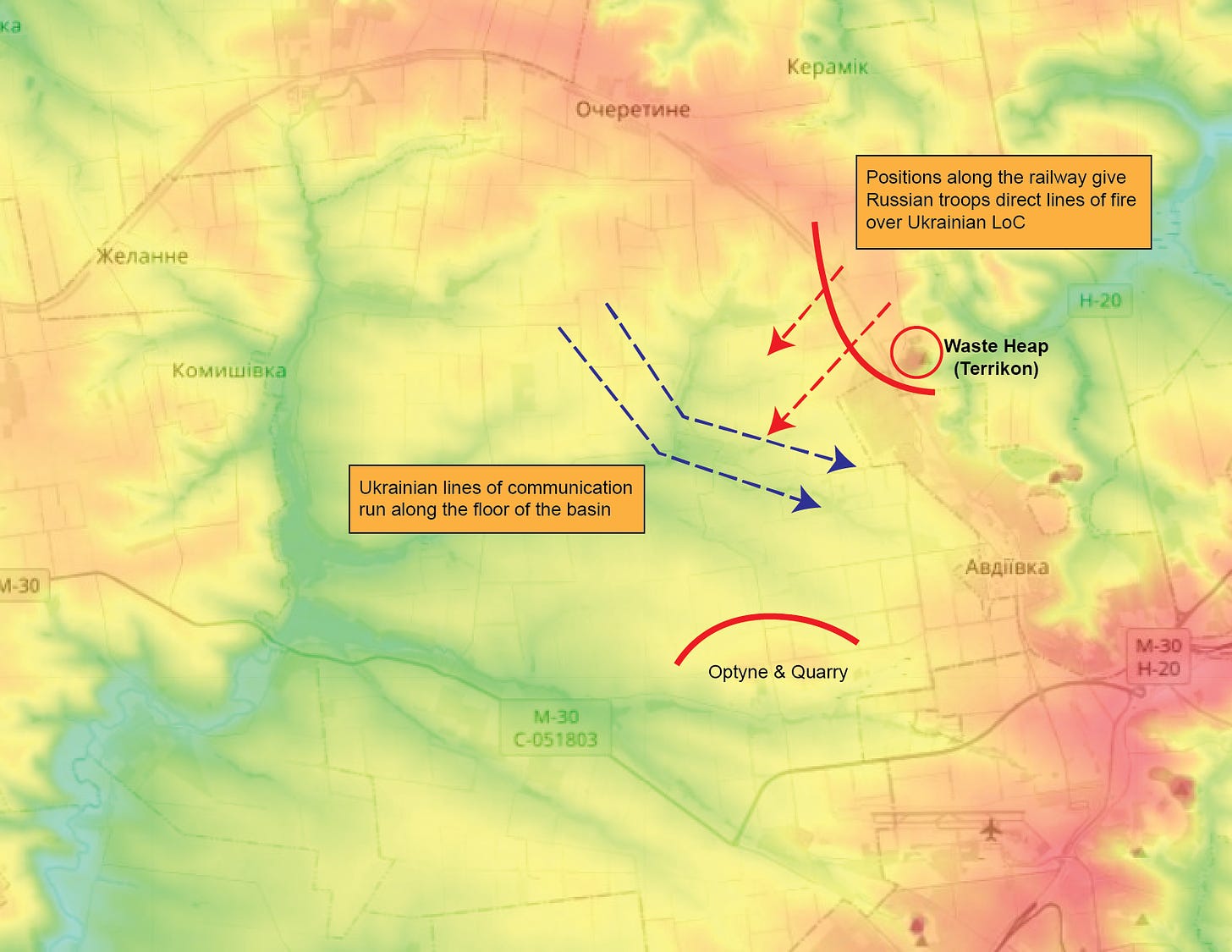

In fact, Avdiivka is clearly a locale with great operational significance. A Ukrainian fortress since the beginning of the Donbass War in 2014, Avdiivka served as a keystone blocking position for the AFU on the doorstep of Donetsk, sitting on a major supply corridor. Its capture creates space for Russia to begin a multi-pronged advance on next-phase Ukrainian strongholds like Konstantinivka and Pokrovsk (more on that later) and pushes Ukrainian artillery away from Donetsk.

The subject that would seem to be of particular importance, however, was the manner in which Russia captured Avdiivka. The struggle amid the wreckage of an industrial city provided something of a Rorschach test for the war, with some seeing the battle as yet another application of Russian "meat assaults", overwhelming the AFU defenders with mass amid horrific casualties.

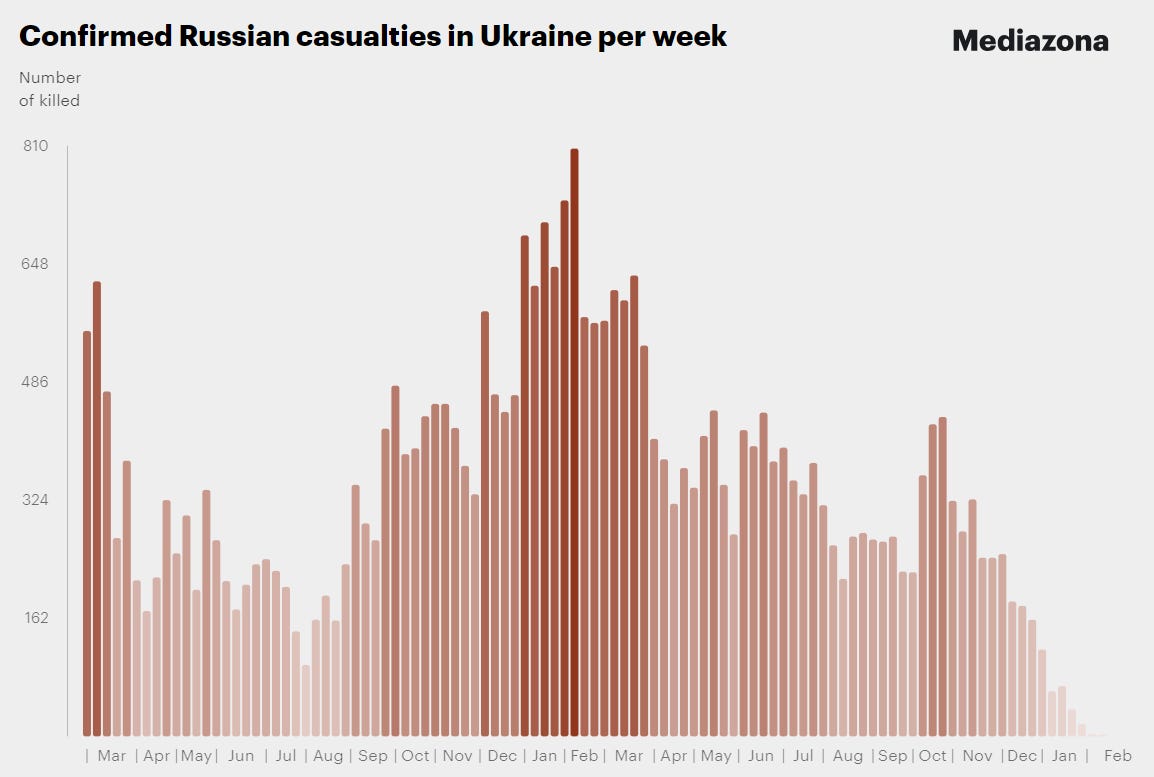

This story does not hold up to scrutiny, as I would like to demonstrate from a variety of angles. First, we can try to gauge casualties. This is always difficult to do with a high degree of accuracy, but it would be useful to look for abnormalities or spikes in Russian loss patterns. The most widely accepted source for this would be the Mediazona casualty tracker (an explicitly anti-Putinist media project operated out of the west).

When one goes to examine the Mediazona counts, an interesting discrepancy manifests itself. The summary text notes that a four-month battle for Avdiivka has recently concluded, and Mediazona states: "We are seeing significant growth of Russian casualties since mid-October." This is actually quite odd, because their data shows the literal opposite. Since October 10 (the day of the first major Russian mechanized assault on Avdiivka), Mediazona has counted an average of 48 Russian casualties per day, which is actually significantly less than the burn rate earlier in the year. In contrast, Mediazona counted 80 casualties per day on average from January 1 to October 9. This period, of course, includes heavy fighting in Bakhmut, so if one takes the period between the end of the Battle of Bakhmut and the beginning of the Battle of Avdiivka (May 20 to October 9) one finds an average of 60 Russian casualties per day. A time series of Mediazona's weekly confirmed casualties also shows a downward trend, making one wonder how they can feel comfortable claiming that the action in Avdiivka has raised the burn rate.

Furthermore, Ukrainian sources on the ground emphasized that the Russian assault in Avdiivka was quite certainly not a mere function of mass, and noted effective Russian small unit tactics with a powerful fire support. One Ukrainian officer told Politico: "That's how they work in Avdiivka — artillery levels everything to the ground, and then professional landing troops come in small groups." Another officer described Russian small unit assaults (5 to 7 men) occurring at night. All of this is inconsistent with the trope about Russian "human wave" assaults - which, we should note, have never been caught on camera. Given the Ukrainian fondness for sharing combat footage, oughtn't we expect to see some alleged evidence of these Russian waves being mowed down?

All this is to say, the claim that Russia (yet again) suffered catastrophic losses in Avdiivka is simply not supported. Like a previous analysis in which I showed that Russian armor losses were not rising or showing abnormal patterns, we yet again have a major Russian assault failing to cause a spike in the loss data. This is not to deny that Russia has suffered casualties. The operation at Avdiivka was a high intensity, four month battle. Men are killed and vehicles are destroyed in such affairs, but there is little evidence that this occurred at abnormal or alarming rates for the Russian Armed Forces.

Now, you're certainly free to make your own judgements, and I have no doubt that the belief in massive Russian casualties and human wave assaults will endure. However, to believe this, you must make an epistemological leap of faith - believing that the wasteful human waves exist despite Ukrainian fighters testifying to the opposite, and that Russian casualties have risen in a way that is somehow invisible to trackers like Warspotting and Mediazona.

In contrast, Avdiivka stands out as the first major engagement of the war where Ukraine's growing material shortages have been acutely felt. After burning through much of their accumulated stock (including the large batch of shells purchased from South Korea by the United States), the AFU felt a glaring and painful artillery shortage in Avdiivka. Complaints about "shell hunger" were a motif of the coverage of the battle. Of course, we've heard about the growing shell shortage for months (and it is known that Ukraine simply does not have enough tubes to cover the entire front), but Avdiivka stands out as a keystone position, important enough for Ukraine to scramble premier assets to reinforce it, where they simply could not provide an adequate base of fire.

In the absence of adequate artillery, Ukraine has increasingly tried to lean on FPV drones as a substitute. There is a certain strategic logic to this, in that small drones can be manufactured in distributed facilities and do not require the capital intensive production centers (vulnerable to Russian strike systems) that artillery shells do.

However, drones are clearly not a panacea to Ukraine's problems. In the simple technical sense, the destructive power of an FPV drone (which usually carries the warhead of a rocket propelled grenade) pales in comparison to an artillery shell and is thus unsuitable for suppressive fire or the reduction of strongpoints. Drones are also subject to disruptions from weather and electronic warfare in ways that artillery is not. More importantly, however, Ukraine is simply losing the drone race. Ukraine's achievements ramping up drone production in wartime are genuinely impressive, but the country's industrial base is still far smaller and more vulnerable than Russia's, and Russia's drone production is starting to widely outstrip Ukraine's. Ukraine's weakness in other arms prompted them to be the first party to lean heavily on FPVs, but that early lead has been lost.

So, drones clearly offer a lethal and important battlefield expedient, but they are neither a genuine replacement for artillery nor an arm of clear advantage for Ukraine. The result was a Ukrainian defense in Avdiivka that was substantially outgunned. The problem was compounded by the rapid proliferation of Russian air dropped glide bombs, alongside the degradation of Ukraine's air defense. This allowed the Russian air force to operate around Avdiivka with something approaching impunity, dropping hundreds of glide bombs with the power to - unlike artillery shells, let alone tiny FPV warheads - level the fortified concrete blocks that normally make Soviet vintage cities so durable in urban fighting.

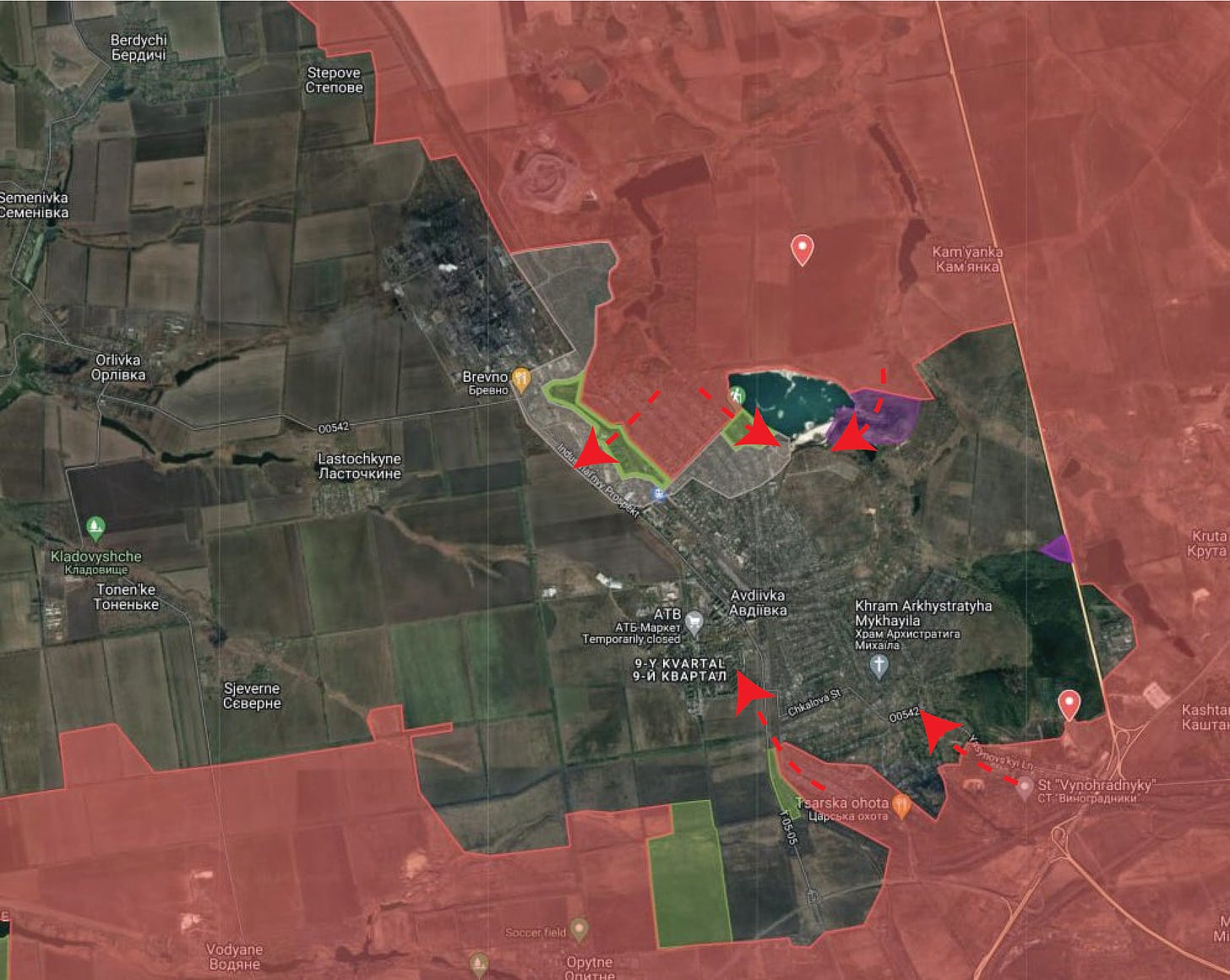

Thus, Avdiivka unfolded along a pattern that is now becoming very familiar, and indicates the emerging Russian preference for assaulting cities, at least of this mid-sized fortress variety. Once again the operation focused in its preliminary phase on flaring out Russian control over the flanks, beginning with the large mechanized assault in early November which secured positions on the railway line to the north of the city. Again (as in the case of Bakhmut and Lysychansk-Severodonetsk) there was an expectation among some that Russia would attempt to encircle the city, but this still does not look feasible in the current operating environment under the nexus of fires and ISR. Instead, positions on the flank allowed the Russians to launch concentric attacks into the city, entering on multiple axes that compressed the Ukrainian defenders into a tight interior position, where Russian fire could be heavily concentrated.

The particular combination of concentric attack and overwhelming Russian fires led to a very rapid end to the battle once the Russian push into the city proper began. While the creep around the flanks occurred in a sequence of on and off pushes through the winter, the concentric crush on the city lasted scarcely more than a week. On February 7-8 the Russians achieved breakthroughs in both the northern and southern suburbs, and by February 14 the Ukrainians were in retreat. A few pockets of resistance would linger for only a few days.

Despite statements alleging that they had conducted an "orderly withdrawal", there is abundant evidence that the Ukrainians were taken aback by the tempo of the Russian assault, and the evacuation was hastily organized and only partially completed. A large number of personnel were unable to escape and are now POWs, and it is clear that Ukraine did not have time or energies to evacuate the wounded, instead ordering that they simply be left behind. The general picture is of a chaotic and ad-hoc retreat from the city, not an orderly and pre-planned withdrawal.

The issue for Ukraine now goes beyond the loss of Avdiivka and the opportunities that this will create for Russia. Ukraine now has proof of failure on both the attack and the defense in operations where they concentrated significant forces. Their counteroffensive on Russia's Zaporhzia Line was a catastrophic failure, wasting much of the AFU's carefully husbanded mechanized package, and now they have a failed defense on their hands in Avdiivka, despite fighting out of a well prepared fortress and scrambling reserves into the sector to reinforce the defense.

The question now becomes fairly simple: if Ukraine failed to attack successfully over the summer, if they could not defend Bakhmut, and if they cannot defend in Avdiivka, is there anywhere that they can find a battlefield success? The dam is leaking. Can Ukraine plug it before it collapses?

Russia's Full Court PressUkraine's force structure is always notoriously difficult to parse out, due to their propensity for ad-hoc battlegroups and their practice of piecemeal allocation of forces to resident brigade commands (turning brigade headquarters into the cups in a shell game). Truth be told, Ukrainian ORBAT and force allocation is in a class all its own - to try and get a handle on it, you can do no better than Matt Davies' excellent work over on X dot com. This generally makes the AFU's organization and force generation more opaque and more difficult to parse out than Russia's, for example. While Russia employs conventional army level groupings, Ukraine does not, and indeed lacks any organic commands above the brigade level.

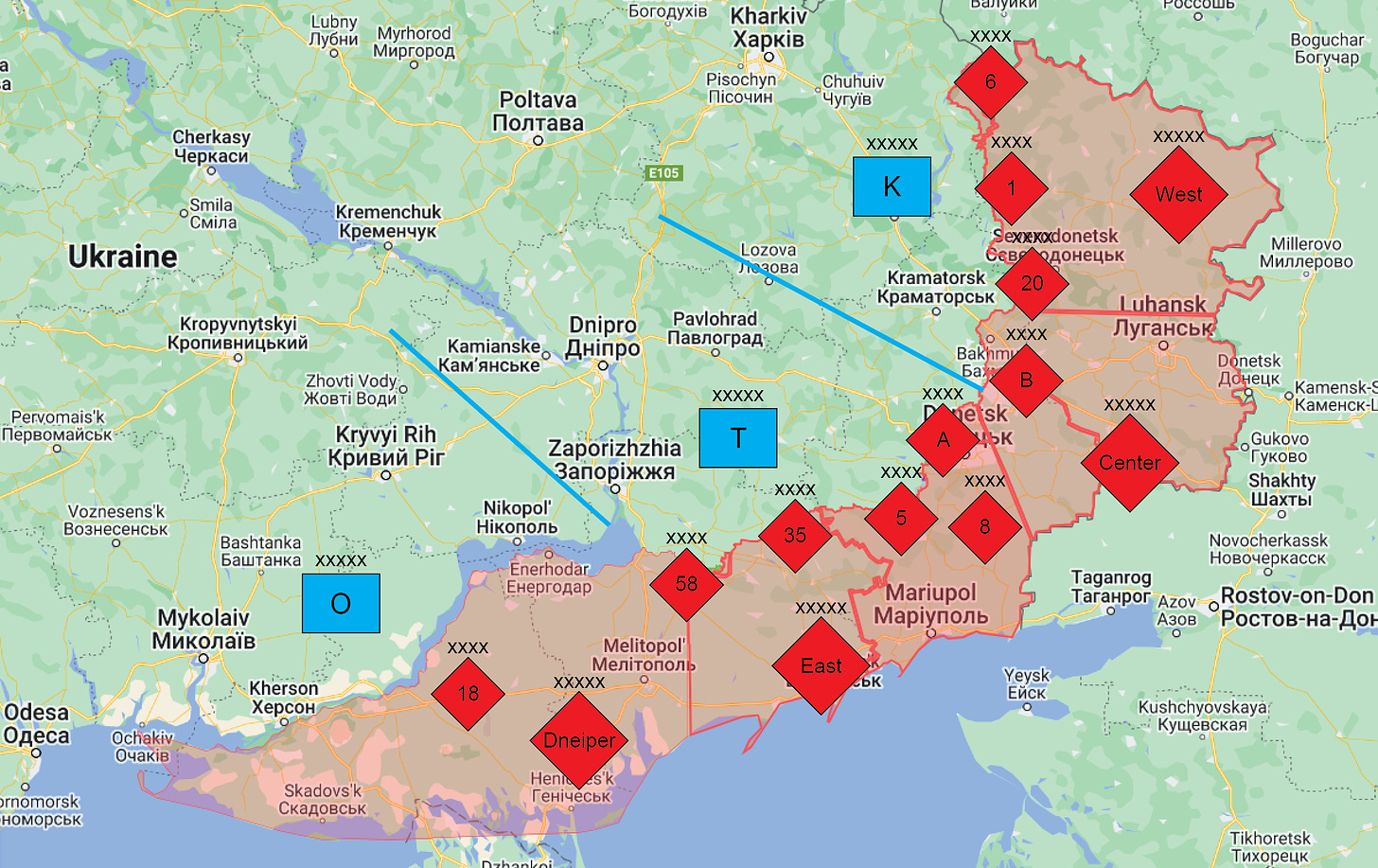

That being said, the basic picture is one of three Ukrainian "Operational Strategic Groupings", which are vaguely akin to army groups. These are, from north to south, Operation Strategic Groupings (OSGs) Khortytsia, Tavriya, and Odessa. Against these are arrayed four Russian Army Groups - from north to south, these are Army Groups West, Center, East, and Dnieper. Assessing the total line strength is always difficult, largely because we do not always have good insight into the actual combat rating of these units. However, we can make estimates of paper strength. Based on deployment information from the Project Owl Ukraine Control Map and the Militaryland Deployment Map, we can estimate that the nominal strength in the theater right now is some 33 Division Equivalents for Ukraine against perhaps 50 DEs for Russia - a significant, but not utterly overwhelming Russian advantage. We get a picture something like this (Ukrainian Army level formations are absent because they do not exist):

At the moment, Russia is grinding slowly forward on almost every axis in the theater. This has both strategic/attritional implications, in that the Ukrainians are forced to continually burn reserves while being denied the ability to rotate and reconstitute units, but there is also a clear operational formulation occurring.

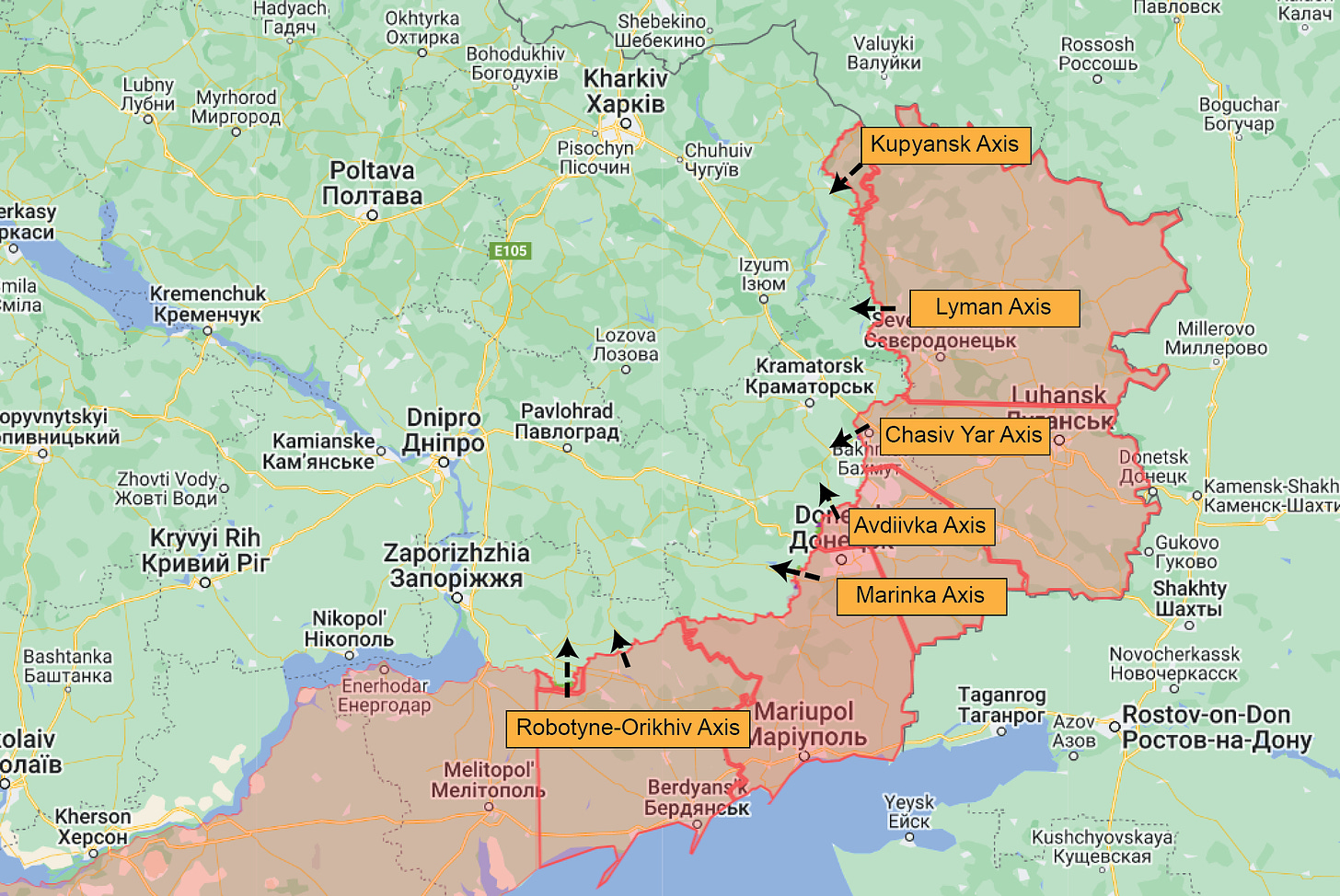

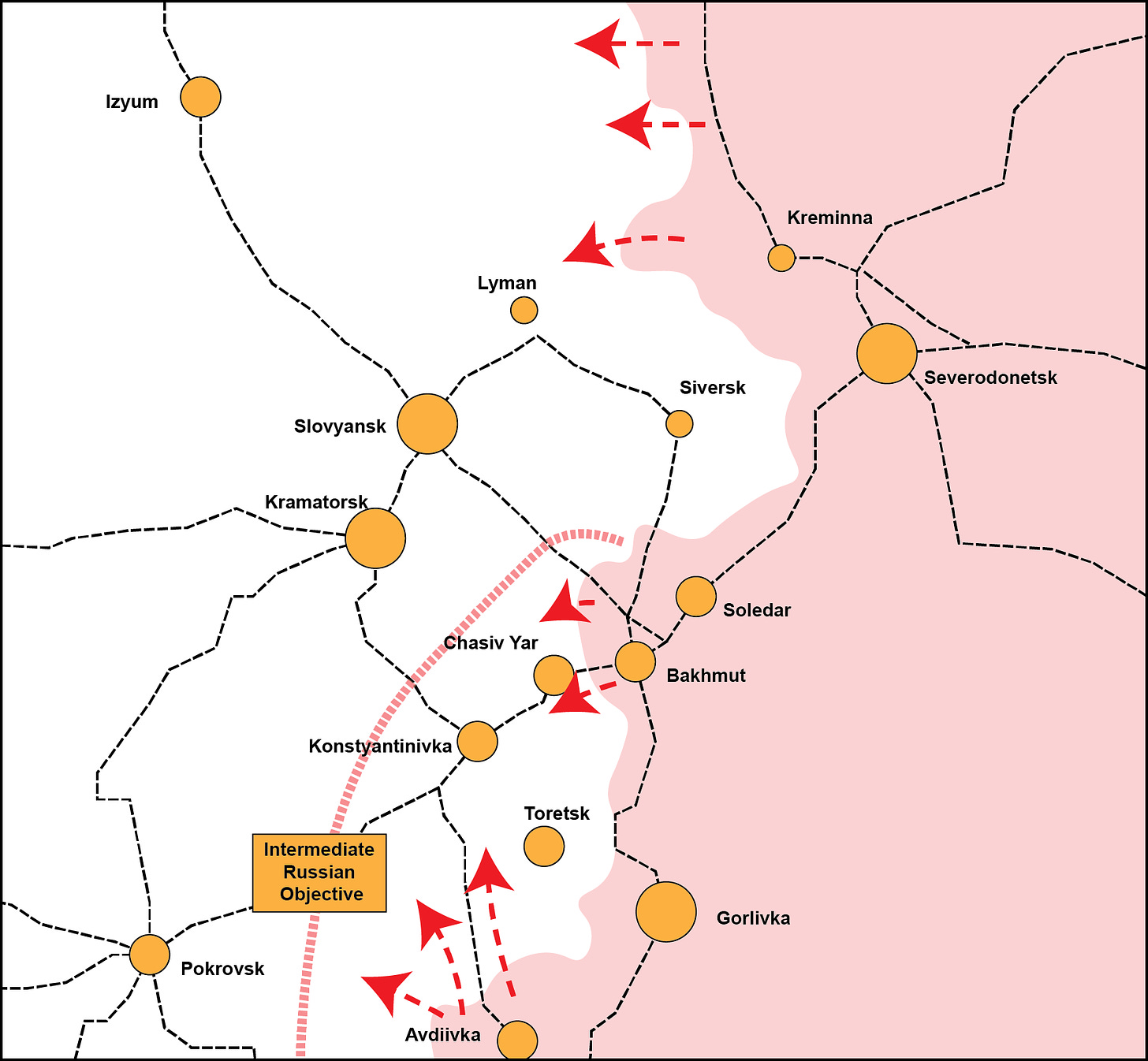

The Russian maneuver scheme must be held in reference to their minimum end state objectives - namely, the capture of the remaining Donbas urban agglomerations around Slovyansk and Kramatorsk (though we should not assume that the war or Russian ambitions end there). At the moment, there are several major axes of advance, which I am labelling as follows:

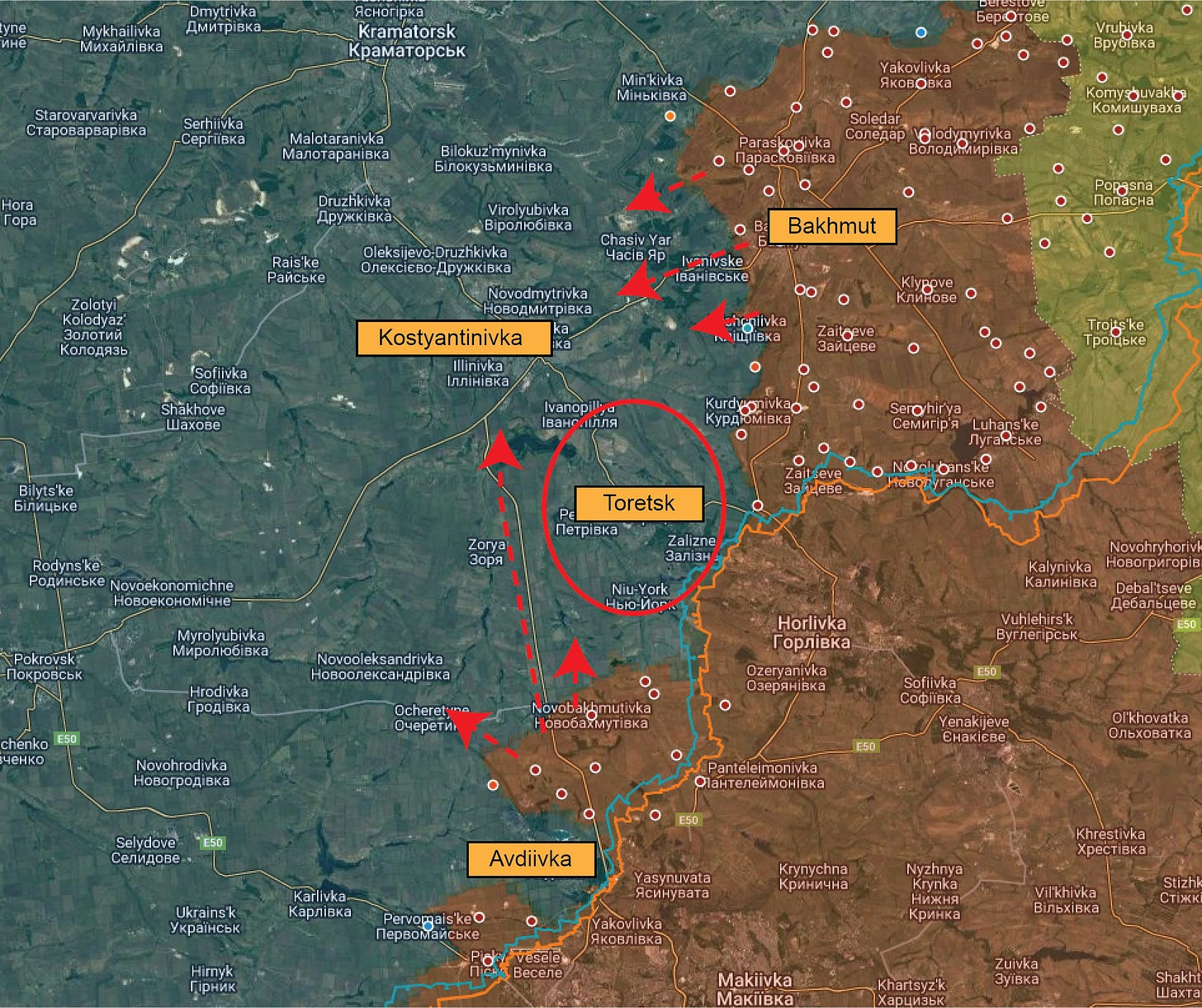

The intention of these thrusts is fairly obvious. In the center of the front, Russian advances on the Avdiivka and Chasiv Yar axes converge on the critical Ukrainian hub of Konstyantinivka, the capture of which is one of the absolute prerequisites for any serious attempt to move on the Kramatorsk agglomeration. Russian bases of control around Avdiivka and Bakhmut provide the necessary space to begin a two-pronged operation towards Konstyantinivka, bypassing and enveloping the strongly held Ukrainian fortress of Toretsk. (See the map below, which I made in December before the capture of Avdiivka).

Meanwhile, continued Russian pressure on the northern front (via a slow squeeze on the city of Kupyansk, at the top of the Oskil line as well as operations towards Lyman on the Zherebets axis) provide a base of progress towards the other operational perquisite for Kramatorsk, which is the Russian recapture of the north bank of the Donets River, up to the confluence of the Oskil at Izyum.

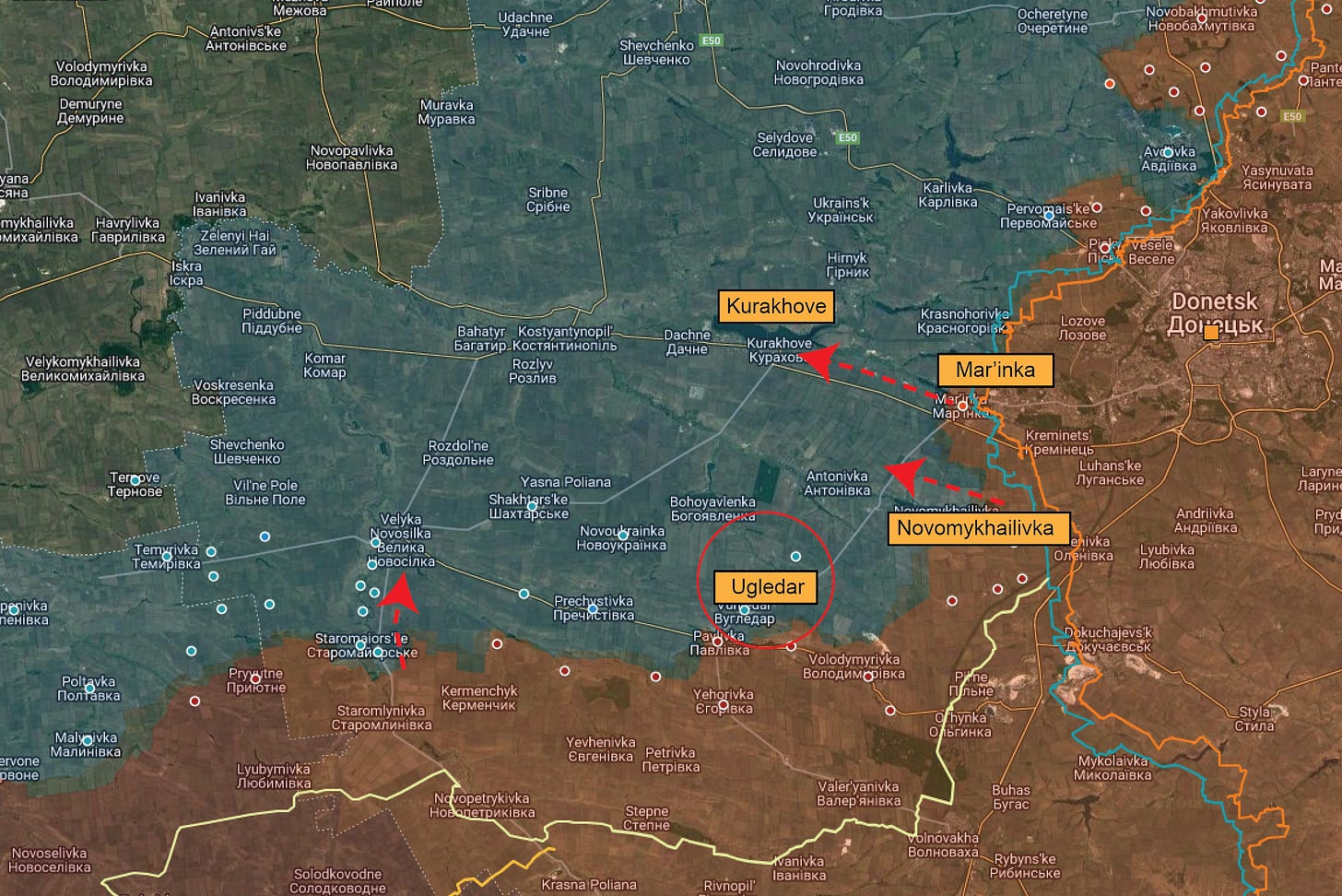

Meanwhile, on the more southerly axes, Russia continues to expand its zone of control after the capture of Marinka, likely with the aim of developing momentum towards Kurakhove, which would put the Ukrainian fortress of Ugledar in a more severe salient. Ugledar remains a thorn in Russia's side, in that it lies uncomfortable close to Russian rail lines into the land bridge. Russia is also attacking the Ukrainian held Robotyne salient (the sparse fruits of Ukraine's counteroffensive). While these attacks have, as we have mentioned, attritional benefits by way of pinning Ukrainian forces in the line, it seems likely that Russia would aim to recapture the Robotyne salient to preempt any Ukrainian designs of using it as a springboard for a future attempt to restart operations towards Tokmak. Thus, these southern operations have both attritive effects and offer the potential of preventatively neutralizing useful Ukrainian staging points.

Overall, the broad operational situation suggests that Russia is developing offensive momentum across the entire theater. This will have deleterious effects on Ukrainian combat power by preventing rotation, reconstitution, and lateral troop redeployment, while sucking in the dwindling Ukrainian reserves. Shoigu recently made an uncharacteristically bold statement that the AFU was committing much of its remaining reserves:

""After the collapse of the counteroffensive, the Ukrainian army command has been trying to stabilize the situation at the expense of the remaining reserves and prevent the collapse of the frontline."